Language is a powerful tool. It can be used to manipulate the opinions of the general public, as with the misnomer of the ‘immigrant’ tag regularly employed by the British press. Immigrant means a person who leaves their country to live permanently in another. The term suggests a degree of choice, which is not the case for refugees. Refugees face persecution or death if they stay; many express a wish to return when things change for the better. The current war in Syria has, according to Mercycorps, killed or displaced more than 11 million people. Amnesty International state that more than 50% of Syria’s population are displaced. The Guardian newspaper reported on a Syrian man who had paid $2,000 for unsafe passage by people traffickers across the Mediterranean; that is a third more than it costs to fly business class from Jordan to Stockholm with Turkish Airlines. If facts and figures are easy to ignore, it is the stories of people which are not.

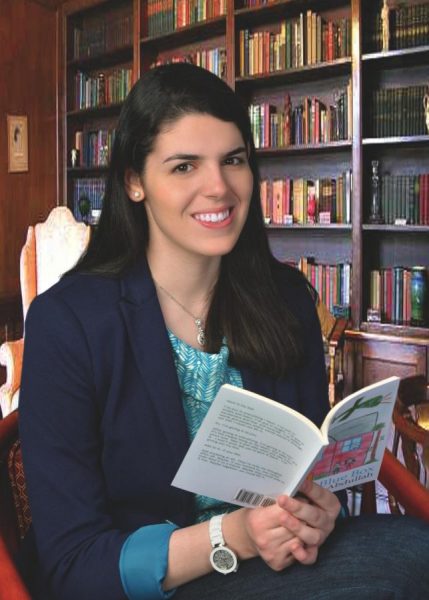

Emma Abdullah was sixteen when she wrote a collection of short stories entitled The Blue Box. The daughter of French and Syrian parents, she was all too aware of the personal consequences of that war. They have lost family members. She has lost friends. As a child herself, what could she do? Children are powerless. But Emma could write, and through her, the truth of Syrian children’s plight will now be heard. The stories she wrote were of situations known to her through family and friends, but seen through the eyes of the children within the war and those trying to escape. “Even the word refugee has so many negative connotations,” she says. “They are people who could have been us.” As a cross-culture child living in several countries, this multiculturalism is, “…key to who I am. When you are part of different cultures that are so different to each other, lots of different cultures play a role growing up and it’s important to find a balance. Western and Eastern can clash a lot but when you are that, it is hard for you to be racist or intolerant in any way because you yourself are made up of contradictions.” Living within an expatriate community, the question people ask is ‘where do you belong?’ Emma replies simply that you have to belong to yourself, because you are made up of the different bits; “Create your own culture. I am a mixture. It’s completely OK. It’s enriching.”

The Blue Box has now been adapted for the stage, a co-operative, cross-cultural effort with Alison Shan Price and Harriet Bushman, and with Arabic direction by Diana Sfeir. The Fringe production raised further funds for UNICEF, the book having already raised close to $80,000 since its publication in 2014. But it was awareness that Emma wanted to raise initially. “If I can make lots of different people aware, then they can go back to their organisations and make changes, make a difference.”

The war in Syria, beginning in the Arab Spring of 2010, slowly seems to have become background noise on the news. However, those who are social media-savvy will perhaps have seen a different story unfold. “This is like the first social media war in the way that Vietnam was the first televised war. People question why a refugee might have an iPhone, but they may have been someone back home [a doctor, lawyer or documentary maker]. Some footage can be shared simply by using a hashtag.” This is how Emma’s generation see it. For the older generation, who rely on television reporting it is a different case. Television media can be used to vilify the refugees for being unwelcome intruders, even as the cause of terrorist activity. “When something is not geographically close to us, though, we may not fully appreciate their existence. I don’t blame them [host country citizens] for it. Politicians and the media manipulate it. So people [refugees] are victims of the conflict, but also become victims of blame for terrorist attacks in host countries. They are stuck on all sides.”

They are indeed stuck on all sides. The situation in Syria is beyond the comprehension of most Europeans. And for the ones who can remember WWII and its aftermath, it is perhaps something they’d rather forget. It is hard to imagine the daily struggle for existence for people who lived in friendly neighbourhoods and had jobs and schooling and markets and entertainment. “The question [for Syrians who stay there] is not if are we going to die but how. It could be the bombs. It could be starvation. Someone could shoot us. We are not getting out. The town is completely surrounded.”

People are listening to Emma. She has gained a place at Stanford University in the USA to read political science and economics, with maybe a minor in creative writing, though so far the book has been well received. She would like to do something in the UN after graduating.

After watching the harrowing version of The Blue Box, I ask how does she process the emotionally wrought situations? “There is optimism,” Emma says. “Because if you have your eyes open you can see what to do about it.” I have a feeling this young woman of integrity and vision will become a driving force on the international stage in a similar way to Malala Yousafzai. Not only are her words a weapon for peace and understanding, she is already giving voice to the powerless children of Syria.