For decades the three political lightning rods have been education, the police and health. For health, read the NHS and although it’s not perfect, heaven knows, it’s a wonder and the envy of many countries in the world.

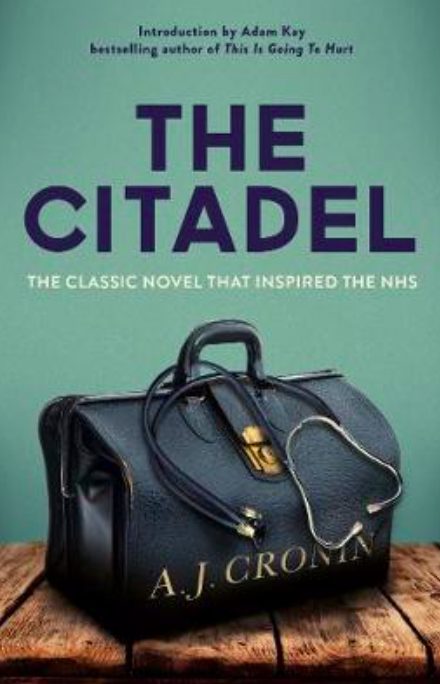

When The Citadel was written in 1937, those who could afford a doctor got one, those who couldn’t, attempted make do and mend themselves. As a young man, Scottish writer A. J. Cronin studied medicine at the University of Glasgow and travelled to take up post as a junior doctor in Wales in the 1920s. That decade saw huge medical advances in terms of surgery, anaesthetics and antibiotics and the profession made great leaps forward.

The Citadel was Cronin’s ninth novel and told of his own experiences in the front line of medical inspection of mines. His bright-eyed hero, the newly qualified Dr Andrew Manson, gains an insight into the lung diseases that affect the miners and the poor housing conditions that affect their families, the questionable ethics of the often mediocre medical profession at the time and the contrast between the miners with life-changing illnesses and the local doctors rooted in discredited, old-fashioned methods. At the other end of the spectrum are the Harley Street “specialists” fleecing and indulging their wealthy, hypochondriac patrons.

This largely autobiographical book is a rattlingly good yarn and was a huge and influential bestseller that helped inspire the National Health Service which was established in 1948. The book has been made (and remade) into films, radio plays and TV movies and is Cronin’s best remembered book.

The picture Cronin paints is unsparing. The heartbreaking infantile cholera, the inexperienced young doctor using a kitchen table for operations while his seniors spend more time on the golf course than tending to tiresome patients. Young Manson does what he can to retain his enthusiasm for the profession in spite of the drawbacks and his staggeringly ignorant colleagues. In the end he leaves the dour mining town for London where he can make a fortune attending to the whims of wealthy patients.

The book is not great literature but Cronin has a way with words and was a born storyteller. He is able to conjure up the look and feel of places and the personalities of his characters in relatively few words and the story whips along nicely. It teeters sometimes perilously close to soap opera but the storytelling is heartfelt.

It’s astonishing to read about a time before health and safety let alone MRI scanners, a time when the local doctor was a notch or two above faith healer. The book often holds up a startling mirror image of the high-tech NHS’s woes of today.