@ Glasgow Film Theatre, on Mon 22, Wed 24 & Thu 25 Feb 2016

(Part of Glasgow Film Festival)

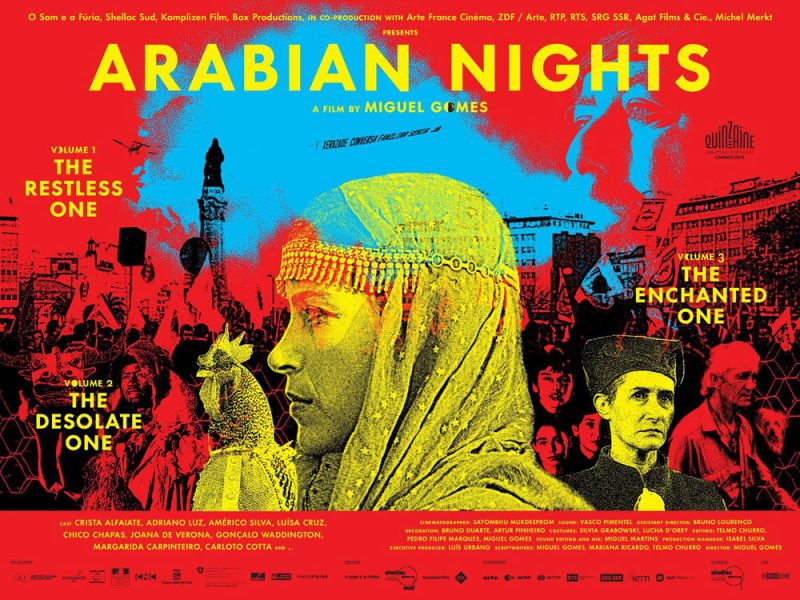

Miguel Gomes / Portugal / 2016 / 120 minutes, 127 minutes, 120 minutes

Memorable moments and great protagonists of national histories are the key substance of epic films and nothing gives rise to heroic deed like a time of crisis. Arabian Nights is a portrait painted as the country still struggles with austerity, and, as Miguel Gomes said at New York Film Festival, it does not contain only factual events, but the people’s ideas of the past, interpretations of the crisis and fears about the future. Such an artistic vision pulls the film in two directions: the recording of social reality on one hand, and the recording of images and stories circulating in popular cultural discourse of a nation on the other.

The journey through contemporary Portugal stretching over three volumes, The Restless One, The Desolate One and The Enchanted One, begins with a visit to the shipyard in Viana do Castelo, whose closure resulted in 600 workers losing their jobs. The national crisis is followed by a personal one when the focus turns to the meditations and doubts of a film director who has decided to record the economic troubles that struck his people. Faced with the apparent impossibility of marrying social realism and fantasy, he flees from his film-making responsibility as a visual storyteller, leaving it to the renowned fictional master-raconteur, Scheherazade, to tell the tale. Her character reveals the significance of the film’s title, incorporating all unwavering storytellers that, through the very act of narration, make known the faiths of others.

The trilogy is built on three levels: fragments of current Portuguese reality related to the economic crisis, Scheherazade’s personal tale and the director unable to make his film. However, the stories that Scheherazade recounts are not all of documentary character. Although real interviews with unemployed people and footage of abandoned factories are abundant, many segments and are of purely fictional character, played out by professional or amateur actors, taking place in undefined locations. At the same time, those stories are made of material from the Portuguese collective imagination, grown from true events or the discourses about true events, and sculpted into another visual narrative.

Scheherazade’s first chapter, entitled The Men with Hard-Ons, sets the stage for Portugal’s “austerity play” giving a satirical account of agreements between the troika – European Central Bank, International Monetary Fund and European Commission – and the Portuguese government. It is not a representation of actual meetings, but a version of events as perhaps some Portuguese might imagine it to have happened. This interplay of reality and fiction is pursued in other parts, such as The Swim of the Magnificents (volume I, part III) combining first person accounts of the tragedy of unemployment with fictional segments of a trade unionist.

It takes less recognizable forms in other chapters because of the local character of the topics. Plenty of references to events featured in mass media and popular culture may go unnoticed by non-Portuguese viewers, but will be immediately recognized by Gomes’ fellow citizens. The chronicle of Simão Without Bowels builds on a widely known episode of a criminal who became a popular hero and was aided by his countrymen to escape the police. Surprisingly enough, the material of one of the most absurd chapters, the public trial containing an endless stream of crimes committed since the beginning of the crisis is directly transferred from Portuguese reality.

At the same time as the trial may seem absurd, due to the scale of criminal activity it reveals, it is the most striking example of Gomes’ multi-layered portrayal of the people. While giving visibility and voice to the disempowered drudging under the Troika’s whip, he does not shy of unveiling their flaws and idiosyncrasies. In this chaotic multitude of misdoings and misfortunes, no one party is denounced as being responsible – the people are neither exonerated of their crimes, but they are also not mere victims of the Troika’s draconic measures. The tableau of Portuguese society is detailed and diverse, avoiding strict polarization between the powerful politicians and powerless people.

The multifaceted portrait results from a process of dismantling factual and fictional events and images and their rearrangement into this melancholic monster-film. Those who appreciate the act of telling as well as the story will be relishing this six-hour piece about Portuguese contemporaneity presented by Scheherazade and Gomes.