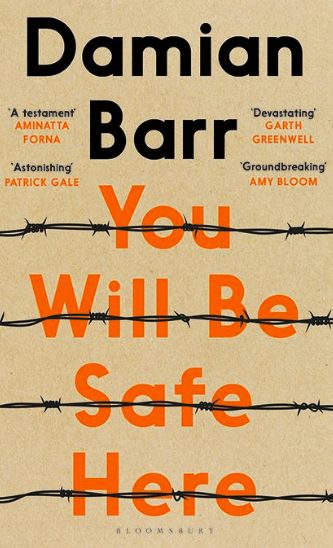

Damian Barr’s first book Maggie and Me was a magnificent memoir about growing up gay in grim North Lanarkshire during the Thatcher era. You Will Be Safe Here, his second novel, also touches on growing pains.

The first part of the novel is set at the height of the Boer War in 1901. Sarah van der Watt, her six-year-old son Frederick, and their servant girl Lettie, are interned in a British concentration camp in Bloemfontein, a shameful part of UK history that is well-deserving of exploration. Barr’s writing is mesmeric and powerful making the story quite riveting but there is not a huge amount of description and explanation, the reader has to work at the plot and it helps if you know your “kraal” from your “Kaffir” and “kopje”. (There’s a helpful historical coda at the end of the book if not.)

Sarah’s unsent letters to her soldier husband Samuel in the form of diary entries show she’s a gritty settler – even when her farmstead is torched by the British soldiers she is determined not to be swallowed up by the loss. At the camp there is typhoid, open latrines, meagre rations and soldiers doling out punishments for infractions. The coins sewn into the hem of Sarah’s dress to buy extras won’t last forever. Still she refuses to sign the oath of allegiance to Britain.

Part two starts in 1976 and tells of Rayna, a young woman who finds brief sanctuary in marriage after the conception of her child Piet, the result of a rape. Her second child, Irma, is also born out of wedlock. She lives in Johannesburg, a city scarred by the demarcations of Apartheid. Irma’s man is away and she’s raising his son Willem with help from grandma. South Africa is changing around them as Mandela becomes president and the Jo’berg crime rate soars.

On a domestic level Willem is showing signs of being a softie. Even at the age of six, when he wants to call the pet dog Britney, his mother worries. As the boy grows older Irma hooks up with a racist security guy, Jan, who feels Willem is getting unmanly traits in a house full of women. A new school of Jan’s choosing will make a man of him. But the school is not what it seems on the surface. Echoes of the 1901 concentration camp are clear.

The book is a kind of 150 year history of South Africa from the farmers who helped make the country prosperous to “post-post-colonialism”. The paramilitary boot camp is set up to radicalise a new generation of white men who will take back South Africa to its former racist “best”. The end of the story does not quite resolve all the elements but the book is a powerful indictment of how aggression and brutality solves nothing and so often only makes matters worse.