Our parents are the making of us – from their DNA to their mad ideas about propriety, of not getting above yourself, not being different. Some of us become cookie-cutter replicas of our parents, others break away. The gifted Deborah Orr was the latter.

Orr left a dull, ordinary, working-class life to become a star columnist, journalist and editor; one of London’s metropolitan elite. Perhaps best known for her pithy outspokenness in the Guardian, Orr had the kind of successful career that many parents would have celebrated but this was not the case for Orr whose constantly belittling mother, Win, often treated her like “a subservient companion” rather than a loved child or autonomous human being.

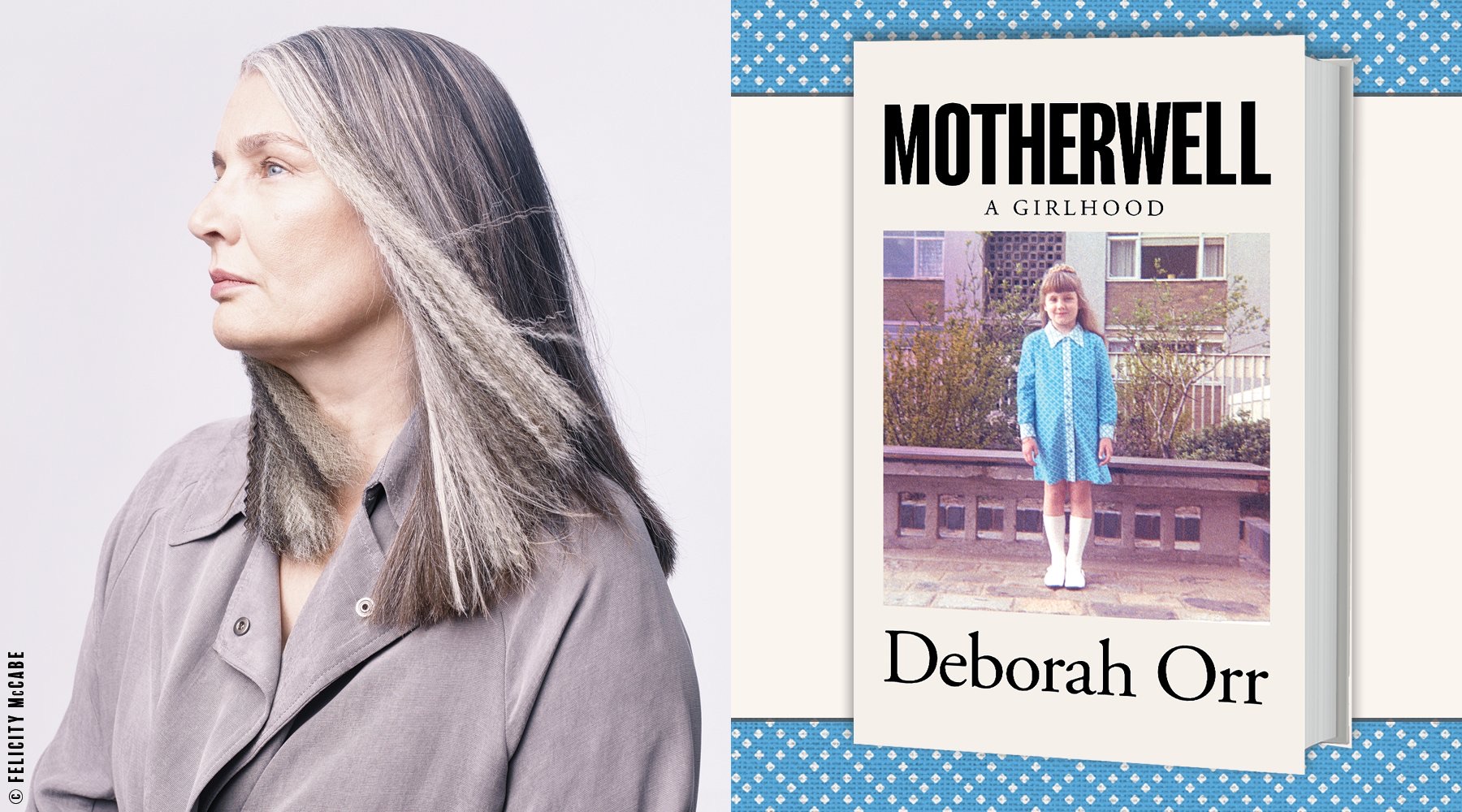

Win was originally from Essex but moved to Motherwell in Lanarkshire where Orr was born in 1963. The Orrs (there was a brother, David) lived an orderly modest life and in this revealing childhood memoir Orr calls her girlhood home “a psychological citadel” where mother knew best, ruled the roost with few arguments and is described as “vivacious and terrifyingly well-organised”.

The author idolised her father, John, an intelligent and handsome man, and she would have had a “fabulous father/daughter thing if it wasn’t for my mum, who came between us.” Orr’s book, although full of vivid observations, often teeters towards out-and-out rant but her litany of woe is leavened by some caustic one-liners.

Just as Orr’s descriptions of her oh-so-average childhood – of aunties and holiday trips and hiding behind the sofa when Doctor Who was on – threatens to take over she indulges in exciting, insightful riffs on how the personal is all too political. She writes about pathological narcissists that do so much damage – be they unthinking blinkered parent or husband. Readers are left to connect the dots.

Later when the Orr family is threatened with rehoming to a newly built tower block there is a fierce denunciation of the 1960s high-rise social housing experiment. The author also attacks other Scottish poisons like sectarianism and toxic masculinity.

But it’s Orr’s mother who Deborah sees most clearly, remembering her quirks and the scars left behind and how this controlling woman very nearly blighted the child. Orr writes that she felt her mother should have, at some point, drawn a line rather than spend the rest of her days grieving the loss of her husband. Little is said of her own rancorous break-up with author, Will Self. Similarly, Deborah Orr should have drawn a line under many of the minor growing pains she endured. If she had, however, we wouldn’t have this rather special book. “Is a memoir therapy or revenge?” asks Orr. Perhaps it’s just her way of drawing a line.