Never have the words ‘I married him’ been uttered with more unfettered triumph and knowing glee than by Rebecca Vaughan’s vibrant Jane in Dyad Productions’ Jane Eyre: An Autobiography. This new play is based on the classic novel by Charlotte Bronte, but the words “vibrant” and “Jane” are not usually synonymous in the context of this tale of an abused orphan-turned-governess in northern England in the first half of the 19th century. Certainly, the character possesses voracious intelligence and a fierce spirit forged in her own private childhood hell, but she is described in the novel – indeed, she describes herself – as ‘poor, obscure, plain and little’. Jane is notoriously hard on herself, especially when it comes to stifling any nascent ideas that her employer, the archetypal “dark and brooding” Mr Rochester, could harbour any romantic feelings for a poor little governess.

Happily, there is nothing poor or little about this show. The script by Elton Townend Jones is nothing short of marvellous, and the consummate skill with which he condenses such complex source material to an hour and a half pales only against the seemingly effortless way he makes it sing onstage. This is no costumed reading of a book upon the boards, nor a monotonous monologue, but rather a full-blooded, vein-tingling theatrical adaptation that more than earns the title “play”.

Townend Jones’ own direction facilitates this process, but – as with all the best productions – it is difficult to tell where his creative input ceases and Vaughan’s wonderful performance begins. And it is wonderful: the kind that stays with you for days after you wear your hands out in applause, as this audience, without hesitation, emphatically do. The stamina and effort alone required to sustain such a lengthy solo performance are remarkable, but there is more – much more.

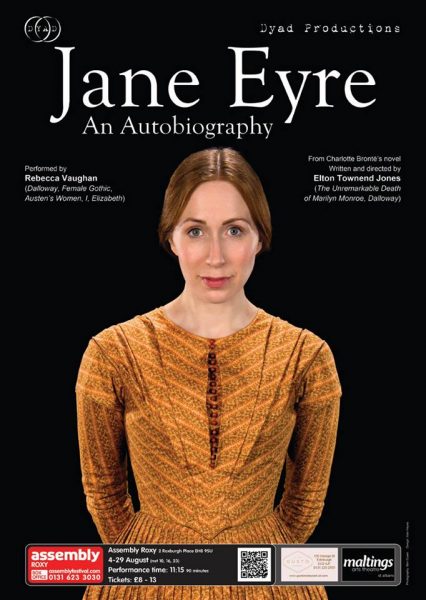

Aesthetically, Vaughan’s apparel and environs embody Jane to a tee: Jane herself would be content. Her dress is plain, her hair is plain, even the set is plain – this latter providing a highly effective foil against which Vaughan’s voice and Townend Jones’ script can soar. But here Jane’s puritan self-image and the true nature of her soul (and that of the play) part ways. The true power here, as with Bronte’s source material, lies in the writer’s unrelenting willingness and Jane’s innate need to shatter the illusions of societal division by socio-economic class, championing instead the ties of the soul and intellect over those of status and sex. Vaughan’s own power as a performer stems from her ability to plum these depths of her character’s soul and lay them bare upon the stage.

At a key moment in the play, Jane declares, “He’s not of their kind, he’s of mine.” Earlier still, “I am a free human being with an independent will.” She is Rochester’s equal, and he is hers. That triumphant declaration of marriage at the climax is therefore commuted from the simple romantic story resolution it would be in, say, a Jane Austen text, and becomes instead a fierce declaration of both liberation and equality.

There is nothing whatsoever obscure about this production. It is an intellectual and spiritual liaison between writer and actor and audience, which plays out at a tremendous pace – only letting up at the final crescendo – and which transcends the artificially-imposed barriers of time, page, class and stage to speak directly to the audience’s soul – if, that is, they have the wit to listen.