Edinburgh- born journalist and writer, Neal Ascherson’s Neil Gunn Trust lecture promised to examine ‘the attitudes of Scottish writers in recent centuries to power – from royal power down to the power exercised by chiefs, landowners, and Big Men in small towns’. How has the notion of loyalty affected Highland and Island writers? Has the power of weather and sea encouraged fatalism?

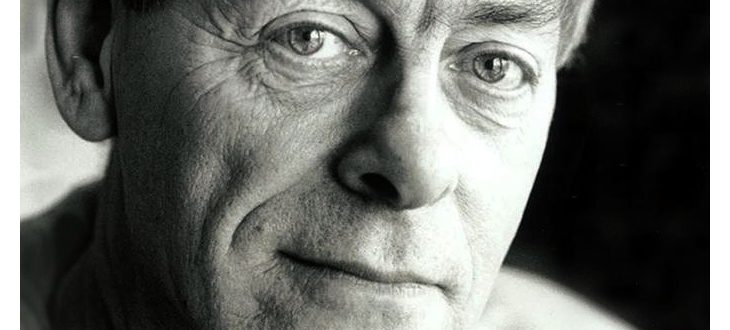

The Onetouch Theatre at Eden Court is reasonably well attended tonight, although the demographic is older than usual. After an introduction about the history of the lecture and the Neil Gunn Writing competition, the guest speaker Neal Ascherson takes the stage.

It takes a little while to get used to his understated delivery – verging on monotone and without visual aids of any kind, following his complex argument takes a fair bit of concentration, and while he makes an effort at the beginning to maintain some sort of eye contact with the audience, the majority of the lecture is delivered fluently reading from his notes.

There is no denying Ascherson’s intelligence, nor can anyone cast doubt on the breadth of his references, spanning Scottish writers over several centuries. He begins with a quote from the Robin Jenkins novel Fergus Lamont, where a character warns: ‘It is a mistake to study the history of one’s own country. It divides.’ Is this true? The Scotland Jenkins knew at the time of its publication in 1979 was one of frustration with political power.

Ascherton argues that, for too long, Scotland’s literature long held on to a kind of nostalgia of loyalty and obedience. With reference to national identity, assertions of Scottish confidence and strength are rare in the history of Scottish writing, and there is a perpetual tension for many Scots writers who depended on the patronage of the rich and powerful (and had to flatter them accordingly) while proclaiming ‘a man’s a man for a’ that’- egalitarianism. But alongside the tradition of conformity came the ‘literature of outbreak’, a rebellious and provocative new writing, finding an identity in victimisation. Finally, as we move into this current phase of writing in Scotland, our country has at last become ‘a normal country, no longer obsessed with victimhood. It has begun recognising its own crimes. It’s a healthy emancipation.

While all this is thought-provoking, it does lack liveliness. Surely the questions will provide some much-needed spontaneous dialogue.

The first questioner doubts the truth of the violent Sutherland Clearances reports, and Ascherton counters his argument with grace. However, despite amplification, the speaker has trouble hearing audience questions and answers a question about Neil Gunn’s fiction of self-discovery with a baffling response about the author’s views about the Soviet Union. He freely admits not to be an expert on Neil Gunn’s writing, drawing some grumbles from an (admittedly purist) audience. All that remains is for the Neil Gunn Writing Competition to be officially declared open, with Michel Faber announced as the head judge. The speaker is a likeable man. Overall, however, the event strikes an uneasy balance: informality and haphazard charm, mixed with the intellectual rigour of academic discourse. I’m not sure it quite worked for me.