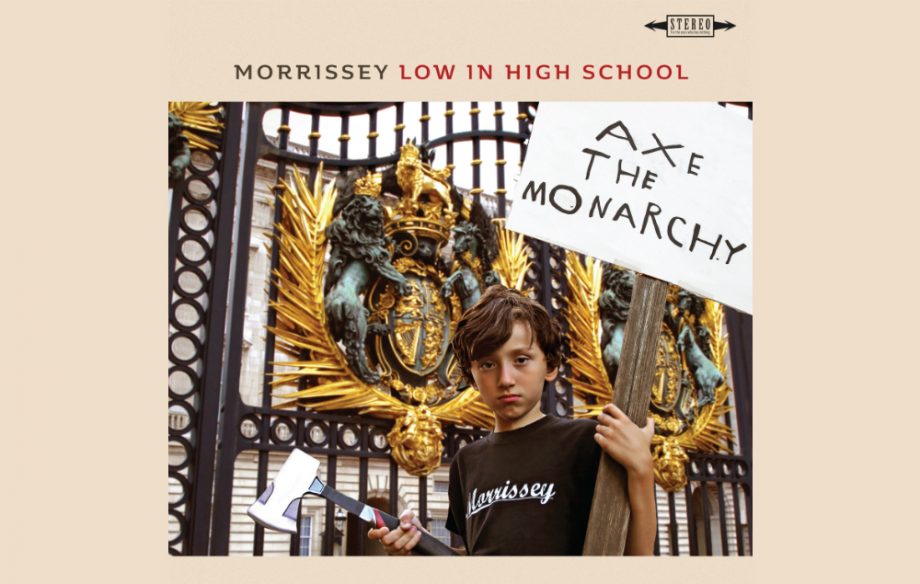

(BMG, out now)

Morrissey has rarely been less popular than today. Not since his first spat with the NME wrote off most of his late 90s output. Now, once again, Morrissey has said some things. And some other things. And yeah, some more things. Things that have even famous acolytes shaving off their quiffs and chucking their gladioli on the bonfire.

What does it amount to? Well, Moz has always given voice to the disenfranchised Northern working class, so for his opinions to hit metropolitan ears as “racist” is not news. It’s also applying literal interpretation to the outbursts of a habitual contrarian, who may just be trying to lob a stink bomb into the chattering class’s drinks party. Stars making ridiculous and preposterous pronouncements are nothing new, and Moz has always had more continental hot-bloodedness about him than you’d imagine from the repressed Englishness for which he’s famed. Fortunately, you can both disagree with him, and listen to his music, if you so choose. Besides, in this age, finding a male star is only a bit UKippy should be a relief.

And, as it happens, those former fans that have now turned a deaf ear are missing his best work for a decade.

Low In High School finds some beautiful and, importantly, new musical settings for his increasingly fragile vocals. Even on his celebrated comeback, You Are The Quarry, the music, catchy though it was, sounded dated and stodgy. The best tracks on recent albums have flirted with other idioms – piano balladry, heavy orchestration, glimpses of an inner chansonnier. There’s more of that here.

But not until the second half. To start with it’s Mozness as usual. My Love I’d Do Anything For You is a stompy, statement-of-intent opener in the mould of You’re Gonna Need Someone On Your Side. I Wish You Lonely sounds like it came from the 80s, but not the one Moz originally inhabited. Possibly the one A-ha were in. Jacky’s Only Happy When She’s Up On The Stage is plodding filler, a poor choice for second single.

Lyrically, he’s still anti-authority (see “Tombs full of fools who gave their life upon command / Of monarchy, oligarch, head of state, potentate” on I Wish You Lonely) and self-pitying. We knew he Spent The Day In Bed, but he’d also “like to be rotted out just before I become aware of the pain,” (from My Love, I’d Do Anything…)

Things get interesting with pacifist parable, I Bury The Living. The deliberately colourless verses allow focus on the lyrics (“I’m just honour-mad, cannon fodder”) and lead to a beautiful coda, from the playbook of his old guitarist Vini Reilly, over which a brittle Moz sings the cry of a pining mother, “Funny how the war goes on, without our John”. In Your Lap appears to be a call for love in the hell of a war zone. And while the title raised a few panicked eyebrows, The Girl From Tel Aviv Who Wouldn’t Kneel appears to be a feminist celebration – a song of female defiance in the face of aggressive masculinity. “What do you think all these armies are for? Just because the land weeps oil”. Its piano flamenco makes another good foil for Moz’s voice, as does the klezmer sway of When You Open Your Legs.

It’s inadvisable for anyone to be making pronouncements about the Middle East, unless they have some peace-keeping role to play, so the sight of Israel on the track-listing sent chills down spines. However, if you can set politics aside, Morrissey’s main target on the track seems to be the constrictions of religion on the individual: “You realize, if you’re happy / Jesus sends you straight to hell?/ And should you dare enjoy your body / Here tolls Hades’ welcome bell” and “Nature gave you every impulse / Who are virgin priests to tell / How to love / How to live?” Melodically and atmospherically, it makes a splendid closer.

The album’s weaker numbers all have Boz Boorer on co-writing credit. Who Will Protect Us From The Police? could easily be dropped entirely. One day, as he ages, Morrissey will drop the last vestiges of indie rock, and make a whole album of understated weepies. It’s these that suit him best now.

Reports of Morrissey’s cultural death though have been greatly exaggerated. Despite recent reactionary pronouncements, there are, even on this, some signs of the empathy for the dispossessed with which he used to excel. He’s in a critical depression, but there could be one last great flowering ahead in early old age. Let’s hope so. He might currently be music’s gibbering, daft old racist uncle, but we’ll miss him when he’s gone.