Back in the noughties, the late lamented Word magazine mused on what the optimum level of musical fame would be. Not Beatles famous, obviously, where you can’t walk down the street. But not cult famous either – critically lauded, but with gig and record sales that keep you in penury. No, the person they settled on, the one in the Goldilocks zone of fame, was this man – Nick Cave. The cognoscenti all loved him, he sold reasonably well, but he was still ripe for others to discover. And should a newcomer discover him and find he was playing their city next week, they’d probably still be able to get a ticket. He was big, but not that big. Alternative, but not that alternative.

That was then, this is now.

Everyone loves Nick these days. He’s genuinely cherished, however uncherishable he may once have seemed. Twenty years ago you could see him at the Queen’s Hall. Now, he’s an arena act.

There’s various reasons for this. He’s a survivor, obviously, and gets the elevated status given to anyone who exhibits longevity, especially someone with demons like Cave’s in their past. There’s the way he’s opened up on his Red Hand Files website. “You can ask me anything,” he says, sharing himself like a best friend and dispensing wisdom like a guru. There’s the occasional out-of-character puncturing of his persona, like the time he was spotted waving a foam hand and singing along to Chico Time. There’s the sympathy extended to him following the death of his son, Arthur, in 2015. And then there’s his music. With his sleazy side seemingly blood-let via the Grinderman side-project, this decade has seen him release a trilogy of delicate, intimate albums with a worldly fragility to them. They’ve done well for him. Skeleton Tree was almost a number one.

Ghosteen is a worthy companion to its predecessors, but perhaps even more demanding of total immersion. These are not songs to be encountered casually. They need concentration, and possibly a darkened room.

Much has been made of the impact of grief on Cave’s recent output, and the sombre tone of some of the album is inescapable. But he’s a craftsman and these are works to be appreciated separate from their maker. Knowledge of his personal sadnesses is neither needed nor helpful. Even when his personal life was most obviously mirrored on an album – the Polly Harvey break-up inspired The Boatman’s Call – that detail was extraneous to appreciating the songs in their own right. The same applies to Ghosteen.

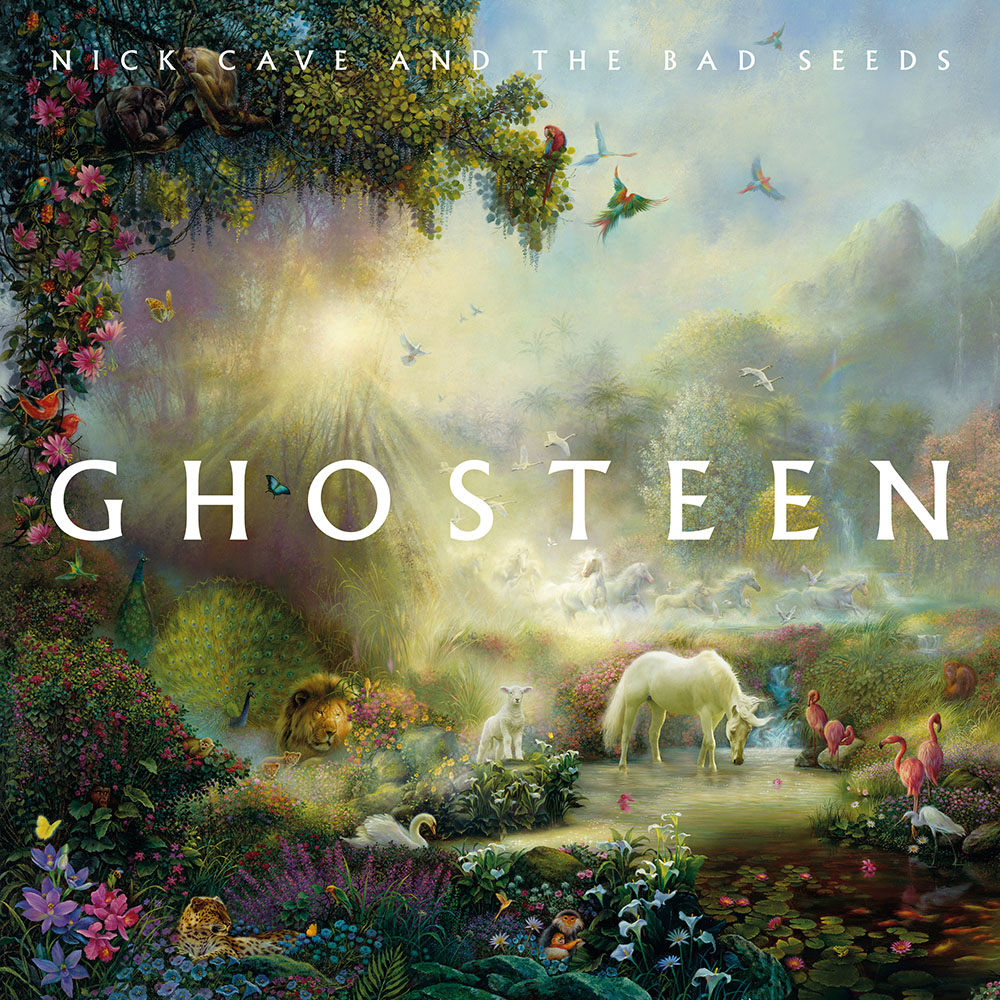

The fantastical cover art – gorgeous, but so ridiculously dreamy, that had the Cave of 30 years ago used it you’d have sworn he was taking the piss – is actually a fair guide to what’s within. There’s deep optimism and positivity here. Of a religious kind: when he sings ‘peace will come’ on the opening Spinning Song, you almost expect it to be followed by ‘and peace will go’, but no, it repeats, like a mantra, like divine assurance. And there’s optimism of a personal kind, too: Bright Horses‘ ‘my baby’s coming back now, on the next train’ is Brill Building cheesy as a couplet, but delivered by Cave, it pure warms the heart. The lush strings help too, like Cave doing Small Change-era Tom Waits.

At its heights, what lifts the album are its uncharacteristic elements, the bits that remind us this is new Cave we’re listening to, like the hitherto unsuspected falsetto on Spinning Song, or the massed backing vocals that occur throughout. You’d hesitate to call them choirs of angels – they’re not always pretty enough for that – but there is an ethereal quality to them.

And chief among the novel elements are the synthesisers that have been quietly surfacing in Cave albums of late, but are now the defining sonic element. Guitars are almost completely absent. Spinning Song‘s simple electronics hark back to the cold, precise electro pioneers of the 1960s and 70s. Leviathan meanwhile is Eno-esque.

Conversely, what almost undoes Ghosteen is Cave at his most Cave-like – that Old Testament pall in his voice weighs too heavy on the album’s otherwise delicate frame. Waiting For You sounds like a Boatman’s Call out-take zhooshed up with more contemporary sounds. It’s pleasant, but feels ploddy for Cave’s 2010s incarnation. Similarly, Night Raid‘s vaguely industrial buzz and stately bell-like clangs seem to call for something more sprightly than Cave speak-singing about checking into Room 33 of the Grand Hotel.

Sun Forest encapsulates these two sides of the album in one song – a pedestrian verse bursts into something heavenly and wondrous. In that case, the light and shade contrast works, but across the album it’s clear that it’s the light that’s bringing the beauty. The musical darkness that has served Cave so well before feels weary and uninteresting here.

Ghosteen is a double album too and Part Two tips it over into self-indulgence. An abbreviated version of the meandering 12-minute title track might make a good closer if it didn’t follow an entire album of similarly-paced material, but the spoken word track Fireflies is collectors-only stuff and Hollywood, even forgetting the title, sounds like film soundtrack material. The whole exercise is an unnecessary thirty minute addendum to an otherwise perfectly fine eight song set.

That won’t stop Ghosteen being loved, especially now Cave’s entered his (inter)national treasure years. The man is not capable of putting out a bad album. Nor can he stop pushing his craft in new directions. His muse takes him where it will. There have been more striking moments in that long career of his, though. This feels like the end of a trilogy, not another new dawn.