The pleasures afforded by the wuxia genre are various, from the small details — the incredible Foley work — to grand narrative designs and quick, precisely choreographed fight scenes. But there’s something deep at work in these films. It’s in the most recent examples, in Hou Hsiao-hsien’s masterpiece The Assassin, with its long passages of stillness or slow movement, followed by intimate and alarming flurries of combat, or in the intricate politics of Zhang Yimou’s Shadow. This depth is explicitly a part of plot in Raining in the Mountain, the 1979 film by wuxia legend King Hu.

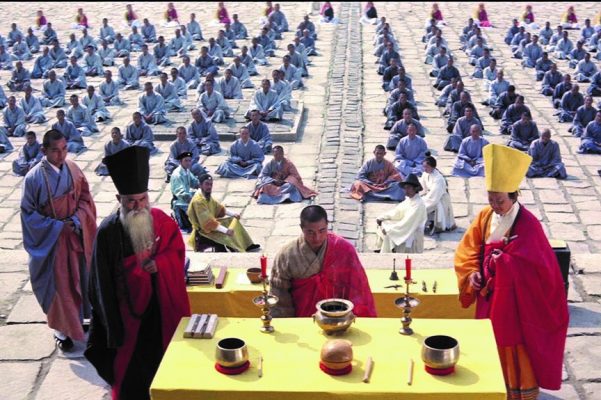

Set in the Ming dynasty, the film concerns the retirement of the Abbot of the Three Treasures Temple; in order to arbitrate over who should replace the Abbot, three outsiders are invited into the temple: Esquire Wen (Sun Yueh), one of the temple’s financial backers; General Wang (Tien Feng), commander of nearby military forces; and (most delightfully) Wu Wai (Wu Chia-hsiang), a lay Buddhist who has excelled himself in his knowledge of the sutras — his ironic deliberations are among the film’s chief pleasures. But there’s more to interest the gathered parties than only the Abbot’s retirement.

The temple houses The Mahayana Sutra, part of the Pali canon, a scroll described by more than one character more than once as “priceless.” Wen and Wang both have plans to steal the scroll: Wen is accompanied by a woman he claims is his concubine, but is really White Fox (Hu regular Hsu Feng), an accomplished thief, on the trail the second she arrives; Wang has his martial arts expert Chang Chen (Chen Hui-lou) on the same task. Complicating matters further is the arrival of a convict, Chiu Ming (Tung Lin), who has purchased a place in the temple, but proves himself more devout than many of the monks whose home the temple has been for years.

The film has a splendid, frantic energy bordering on the comic; characters’ interests are stacked atop one another, so one action has a lovely, toppling effect on the rest. Deception is key, people aren’t who they claim, and the protracted effort put into the finding of the scroll means the film plays out in part like a heist movie. (There are many scenes of characters skulking around the Temple’s exteriors trying to avoid the detection of monks on their rounds, caught in wonderful widescreen rushes of movement.)

The fights in Raining in the Mountain are more like battles of wit, timing, and chance — something Wong Kar-wai evidently learns in his astonishing wuxia The Grandmaster. The aforementioned Foley work is also so satisfying here: the “woosh” of the combatants’ clothes as they leap through the air; the full-bodied, sharp smack of a blow landed against an opponent.

King Hu’s film is a riot of beauty from the start: a long journey to the temple through vast and misty forests, the colours autumnal and the sunlight breaking through the trees. The cinematography, by Joe Chan Jun-git, frames the action as well as the intrigue with candour and skill, a skill pronounced during the fights, the camera moving as if it were a participant in the engagement, hoping to avoid an assault. This a lively, gorgeously composed film, which posits meaning as true wealth.

Available on Blu-ray now.