At the Edinburgh Filmhouse from Wed 27 March

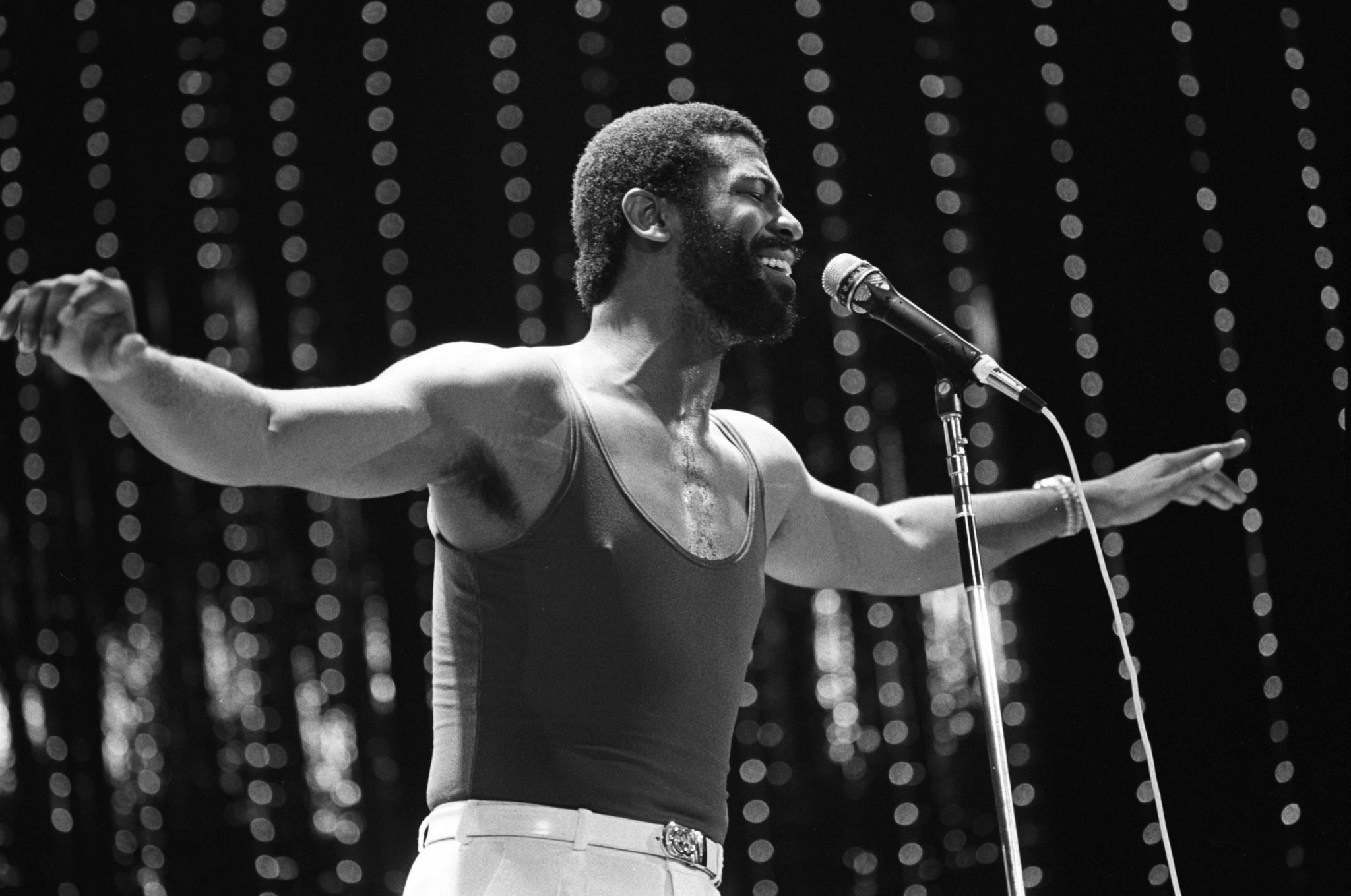

It’s undeniable that the life story of soul legend Teddy Pendergrass has all of the hallmarks and emotional pay-offs of a classic Greek or Shakespearean tragedy. As a result, it is such fertile ground for documentary that it’s borderline unbelievable that Olivia Lichtenstein’s Teddy Pendergrass: If You Don’t Know Me is the first of its kind – an apparently balls-out expose of the life and times of a singer who was at one point billed as “the black Elvis”; a living legend and a sex symbol of seemingly incomparable charisma whose career was tragically cut short in 1982, when he was at his peak of success and fame, due to a horrific car accident that rendered him quadriplegic.

There’s so much to unpack with Pendergrass’ story that is regrettably only very lightly touched upon by the film. The focus of Lichtenstein’s documentary is largely the performer’s late 70s heyday. During this era, once he had worked his way up from small-time player in Philadelphia’s local music scene – an environment controlled and lorded over by the Black Mafia – through his stint as the main singer in The Bluenotes, until finally achieving the universal acknowledgement he deserved as a staggeringly talented solo performer in the late 70s, Pendergrass enjoyed a position that gave him, and those around him, the impression that he was an unshakably powerful and untouchable individual. The terrible accident that has subsequently defined him in the public imagination therefore feels like a tragedy of epic proportions.

Lichtenstein’s film merely hints at the fact that, at his peak, his unique and powerful velveteen vocals were considered by his label and big-name publicists as less of a selling point than his physical presence and his seductive, pin-up qualities, a fact which speaks of a kind of racism, prevalent at the time, that fetishised black male sexuality, and is ultimately reductive and exploitative. This is but one hint at the obstacles that impacted Pendergrass’ life and career that could do with a further, detailed exploration sadly not offered by this film.

Another such avenue is the role of the black mafia in his early career. We are informed that, at one point, before exploding onto the international scene, Pendergrass signed a contract with a manager who was also his girlfriend at the time, a woman named Taaz Lang. We are told he was unhappy with the terms of the contract which, after signing, he felt gave Lang too much power and access to his financial earnings. We are simultaneously told that Lang was, not long after this, shot dead in a case that was never solved. The unavoidable suggestion is that Pendergrass himself had connections with notable local hit-men who may have been responsible for her murder. The film does not offer any definitive conclusion, perhaps, understandably, out of a wish not to defame a man no longer here to defend himself. But the insinuation looms nebulously and uncomfortably over the rest of the film. Some talking heads hint at the idea that his car had been tampered with and his accident was the result of calculated revenge from enemies he made during this stage of his career.

For many audience members, however, the definitive Teddy Pendergrass tale we need to hear may, in fact, relate to none of these things. The essential human story is perhaps the one of his life after his accident. Lichtenstein’s documentary only fleetingly covers his period of intense depression and suicidality once he became quadriplegic. The film summarises that, after navigating a period that could only have been unimaginably hellish, Pendergrass managed to find a way to live a new life, face the future, continue to be a father to his children, and, not least, find innovative ways to continue his musical career. From a modern perspective, this feels like the chapter of most significant human interest. Unfortunately, it all feels pretty glossed over, and in the final minutes of the film, the audience are informed, via some pretty swift captions, of the last thirty years of Pendergrass’ life: he recorded six albums and died in 2010. We are spared the details, as they are presumably considered less salacious than what has come before. This is ultimately to the detriment of the film as a whole. The filmmakers seem unsure about what they are ultimately aiming for: is this a story about a star shot down in his prime? Is it a story about a tragic hero ultimately finding humility and redemption? Is it about the limiting social and political factors affecting a black man in the 70s? Is it about a gangster unable to escape his past?

The life of Teddy Pendergrass is clearly worth several films and documentaries, and it’s fair to say that this offering, while a fascinating introduction, doesn’t quite deliver everything we really need to do its subject justice.

Comments