Showing @ Royal Lyceum Theatre, Edinburgh until Sat 13 Oct

It’s remarkable how incendiary film has been in Québécois society. During the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s, local filmmakers fought with each other over notions of identity, all of them discovering a free consciousness which was distinct from the rest of anglophone Canada. It was during this time that playwright Michel Tremblay saw a Québécois film written in a style of French detached from the way real people talk – in joual. Thus, Les Belles-Soeurs was born.

Tremblay’s 1965 play marked a huge step forward for Québécois artists trying to realise and articulate the need for independent culture; not French, not French-Canadian, but something much more specific. Though he was a front-running figure embarking on such a venture, he shared the decade with filmmakers such as Pierre Perrault, a documentarian who himself moved deep into Quebec, out towards James Bay, in search of the ‘peculiarity of the Québécois parlure’, as writer Paul Warren explained in the 1990s.

It’s hard to miss the opportunity for relocation to Scotland, a nation itself steeped in cultural, linguistic and geopolitical conflict with its neighbouring lands. When Martin Bowman and Bill Findlay first translated Tremblay’s text into fierce Glasgow-Scots, with all the care and political attentiveness required to succeed, something vibrant, globally resonant and deeply sociological was unlocked. While still situated in the realm of francophone Canada, the language couldn’t be closer to our own doorstep.

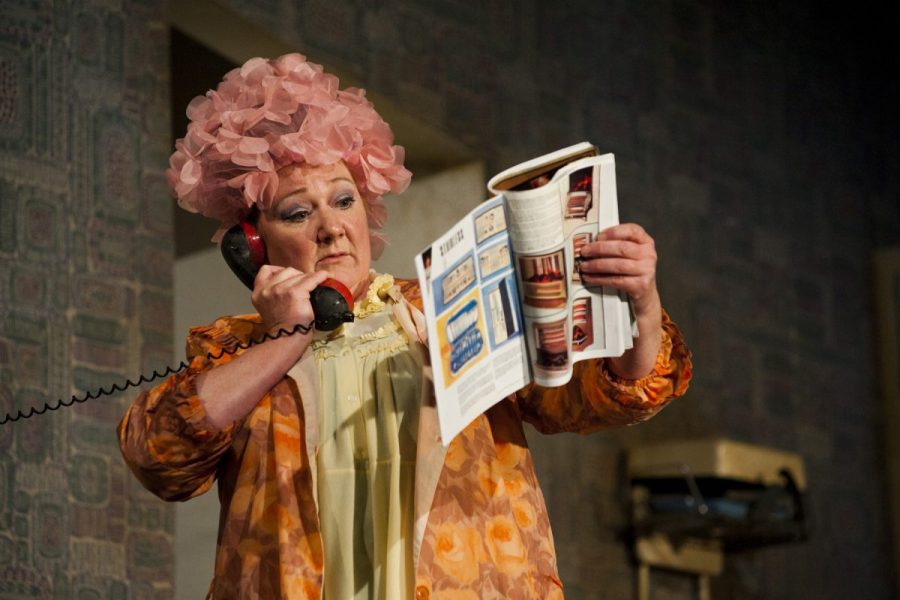

Serge Denoncourt’s production here truly rekindles the fire at the heart of the original text. Following on from the success of his previous cross-cultural project, Imago Théâtre and Stellar Quines’ ANA, the director displays a profound critical awareness of translated theatre. The fifteen-strong cast, made up of some very desperate housewives from Molly Innes’ hilarious, banshee carer to Karen Dunbar’s vulgar jester, pull off a stunning group performance. The women are brought together by a million Green Shield Stamps, as Germaine Lauzon (Kathryn Howden) plans on using the reward scheme offered to redecorate her entire house from the contents of a catalogue.

The bitching and conniving that come when these women collide is at times completely hysterical but often agonising. Soliloquies and asides give an insight into their suburban misery; immobilised by religion, envy, conceit and financial woe, they lash out at each other and constantly seek disruption and gossip. Certain musical numbers about the monotony of preparing breakfast and being ‘daft fae bingo’ could have almost inspired themes in The Stepford Wives, as the women recite lines in choric, almost robotic, harmony.

Tremblay clearly recalled a post-war sense of anger and loss when imbuing his female characters with the level of resentment towards outsiders which the Cold War brewed. Their joint desire to win competitions and somehow pull themselves away from each other is trumped only by their unifying need for enjoyment. Whether in money, love, youth or success, they are all searching for the same ideal which will deliver them from senselessness. Though this can all come across slightly overtheatrical at times, it is vital, ferociously satirical theatre which unites its audience with a 60s society still trapped in dogma and tumult – unlike the romanticised and liberating counterculture period we tend to remember foremost. The absence of politics in theatre can often leave a gaping hole in its sense of place and meaning; Denoncourt’s production captures working-class heroines not in dewy-eyed, sentimental glory, but in tough, earthy and devastatingly accurate circumstances.