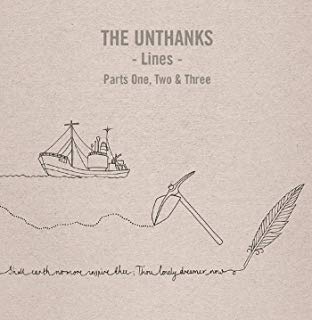

The Unthanks have stopped doing things by halves. As the decade has worn on they’ve seemed ever less keen on producing regular albums, and ever keener on producing what you might call “projects” – themed albums or cross-artform collaborations. Lines is the most esoteric yet, a triptych of works on a theme of poetry and female perspectives. Even then, it’s a fairly loose thread that links 1968 trawler disasters, the First World War and Emily Brontë. Each part requires its own explanation. The music therein is frequently lovely, but it’s an involved listen, if you’re to get the most of it.

Part One is dedicated to Lillian Bilocca, the remarkable Hull woman who took on the government and shipping companies to get safer working conditions for the city’s trawlermen. Last year’s BBC documentary on her and her fellow Headscarf Heroes is well worth a watch, while these particular songs come from a site-specific theatre piece written by Maxine Peake for Hull City of Culture. A Whistling Woman carries some of Bilocca’s defiance and anger in its tense, insistent piano chords and backing vocals that sound like the chants of protesters, but the remainder of the mini-album is rather gentler. It’s bookended by a tumbling piano instrumental that represents Lillian’s “theme”, a motif around which The Sea Is A Woman is also built. Meanwhile Lonesome Cowboy is a sultry, end-of-the-night jazz bar thing whose relation to the theme isn’t immediately apparent without knowing the play from which it was drawn. The shortest of the three medium players, it’s also the most direct and easiest to navigate.

Part Two was originally conceived for a 2014 live audio-visual project, A Time and a Place, as an act of remembrance of World War I. The key track is the mournful seven minute opener Roland and Vera, based on correspondence between writer Vera Brittain and her fiancé, war poet Roland Leighton. Sam Lee takes the role of Roland, Becky Unthank of Vera, with a suitable switch of pace and tone when she enters. Everyone Sang makes use of big, rippling piano chords as a setting for the poem by Siegfried Sassoon, whose Suicide In The Trenches is also adapted. Wilfred Wilson Gibson’s Breakfast segues into a snippet from Hanging On The Old Barbed Wire which is a nice touch. The real chills come from War Film though, which sets a mother’s terror to a skeletal piano track, Rachel stoically delivering Teresa Hooley’s lines: “My little son / rotting in no-man’s land / out in the rain”.

The change of poetic styles and singers on Part Two does come at a cost to cohesion and flow, in the same way it would on a compilation album. The restrictions of the poetry also dictate song structure. Not just in the lack of traditional verse-chorus, but in songs finishing before their time, before the music’s been properly able to breathe. Some clock in at just over two minutes – disjointed snippets of loveliness.

Part Three, based on the poetry of Emily Brontë has the wonderful backstory of having been composed by Adrian McNally on the Brontës’ own piano at the family Parsonage in Haworth and recorded with some of the Parsonage’s ambient sounds – doors shutting, clocks chiming – in the mix. The mood has undoubtedly shaped the music – the courtly waltz of She Dried Her Tears And They Did Smile being a particular example where both timbre and style evoke the setting very clearly. Titles like Deep Deep Down In The Silent Grave give some idea of the tone; a certain darkness not being entirely unexpected of Emily, of course. In parts, it’s pure proto-Goth: “O evening, why is thy light so sad? Why is the sun’s last ray so cold?” Cheer up, love! Could be worse – you could be dying of TB!… Oh. You are.

It’s no surprise that the two modern northern sisters should find a kindred spirit in a famous northern sister of the past. The “thees” and “thous” of the poetry flow quite naturally; it’s a linguistic register not a million miles from the trad folk they’ve dealt in for years. It shares a mood too. The finest moment of the third mini-album is the song from which it draws its name – Lines, a swirling seven minutes of piano in which the pair weave their voices into one.

Those voices, solo or in harmony, remain one of the most captivating sounds in contemporary music and McNally’s measured, minor key piano balladry makes a great setting for them. But because it’s effectively soundtrack work, the charms of Lines are often understated and brief. The meat of the material is to be found in the works that inspired them. These songs are the condiments – tasty, but inadequate on their own. Each of these is crying out to be experienced live, with verbal explanation, or accompanying their original inspirations. Cold, in recorded form, they’re harder to digest, and three courses of Lines are too much in one sitting.