A war film that is as much about the strain of peace as it is the travails of conflict, Bohdan Sláma’s Shadow Country is a drama of scalding nuance and seismic moral turbulence. The dividing line between good and evil is rarely so clear as in World War II. Most narratives are happy to conclude with the Axis powers defeated and righteousness prevailing. Shadow Country examines the effect of the war on a specific area far removed from the main theatres of battle, but already riddled with division. Justice has never looked so qualified, and revenge so empty.

Shadow Country follows the fortunes of a small village on the Czech border with Austria from the annexation of the Sudetenland in 1938 to the aftermath of the second world war. Bisected into two distinct sections, the first covers the war years and the ideological and national split in the area. The second takes place in the immediate conclusion to the conflict up to 1952, with Czechoslovakia’s inclusion in the Eastern Bloc and all the villagers reckoning with their actions during the war. How will they reconcile with the past? How will their future look? And how many still actually have futures?

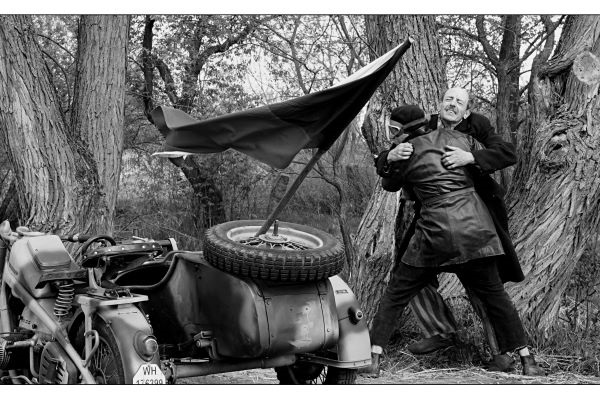

Sláma’s film is a rich ensemble piece that takes its visual and atmospheric cues from the stark landscapes of Béla Tarr and the ominous tension of Michael Haneke‘s The White Ribbon. Divis Marek‘s roving camera traces the families and allegiances, and the fault lines that will soon be levered apart. His gorgeous cinematography is the only thing that is black and white in the film. There are, broadly speaking, two factions. Those who identify as Austrian and therefore side with the Nazis, and those who are Czech and who either submit to Nazi rule through glowering pragmatism, or are forced out as Jews or members of the resistance.

It can be baffling keeping up with the large cast, but a few key players slowly emerge. Veberová (Magdaléna Borová) is a Czech woman married to a German, who is forced out along with all Germans after the war. Resistance fighter Josef (Csongor Kassai) is packed off to a concentration camp, only to return like a vengeful revenant. In meting out arbitrary justice on collaborators he somehow segues from a man armoured by an impeachable moral force into the central antagonist of the second half. Barbora Poláková also finds hidden empathetic beats as Marta, a fervent collaborator who makes herself sexually available to the Nazi officials who set up camp in the town. You would expect her downfall to come with a glorious rush of Schadenfreude. Instead, there is only tragedy and pity.

The theme of division and shifting loyalties in Shadow Country runs right through the very geography of its location. The village was once part of Bohemia, then Austria and then Czechoslovakia. As one villager puts it; ‘I’ve lived in three different countries without ever moving house.’ In a time where there are constant appeals to patriotism – with its sinister cousin nationalism lurking beneath – the film makes clear that such things are unstable foundations on which to pin one’s identity. In 1882 historian Ernest Renan said that nations are based as much on what the people jointly forget as on what they remember. For the villagers in Shadow Country, it’s impossible to see how they can ever coalesce along these lines again.

It is unsurprisingly tough viewing, and will no doubt ruffle the feathers of some who prefer depictions of conflict to be a clear case of good against evil. Interestingly, the vast majority of the violence onscreen is carried out in the second half against the collaborators by the ostensible moral victors. Some who sided with the invaders are nothing more than business owners such as the proprietor of the local pub who continued to serve Nazis and Czechs alike throughout the war. Some meting out punishment to the Austrian contingent are outright villainous themselves such as a man expelled as a rapist who returns as a gleefully psychotic executioner.

Shadow Country, for all its allusions to the greats of East European cinema, most closely resembles Ferenc Török‘s underseen 1945. Sláma’s film is a tonal mirror to that little sepia gem from Hungary, which also deal with the aftermath of the war on a small village. 1945 is shot through with a humanist spirit of reconciliation and aims for emotional catharsis. The Czech film is far muddier in its morality and outright brutal in its depiction of humanity. One is probably more accurate in its assessment than the other. Challenging, searing, and consistently troubling viewing, Shadow Country sees no deliverance in victory or righteousness in revenge. Just the cold, empty destruction of war.

Screening as part of BFI London Film Festival Wed 14 Oct 2020