8:8 makes for both uncomfortable and engaging viewing, although ‘viewing’ is perhaps too distant a term. In a small performance space, a maximum of eight audience members sit in a row as eight performers enter. And stare at us. This goes on for an interminable period and immediately forces the audience to question the mechanics of what is happening, feel awkward, and yet develop some invisible connection with everyone else in the room all at the same time. Eventually, the actors begin to move.

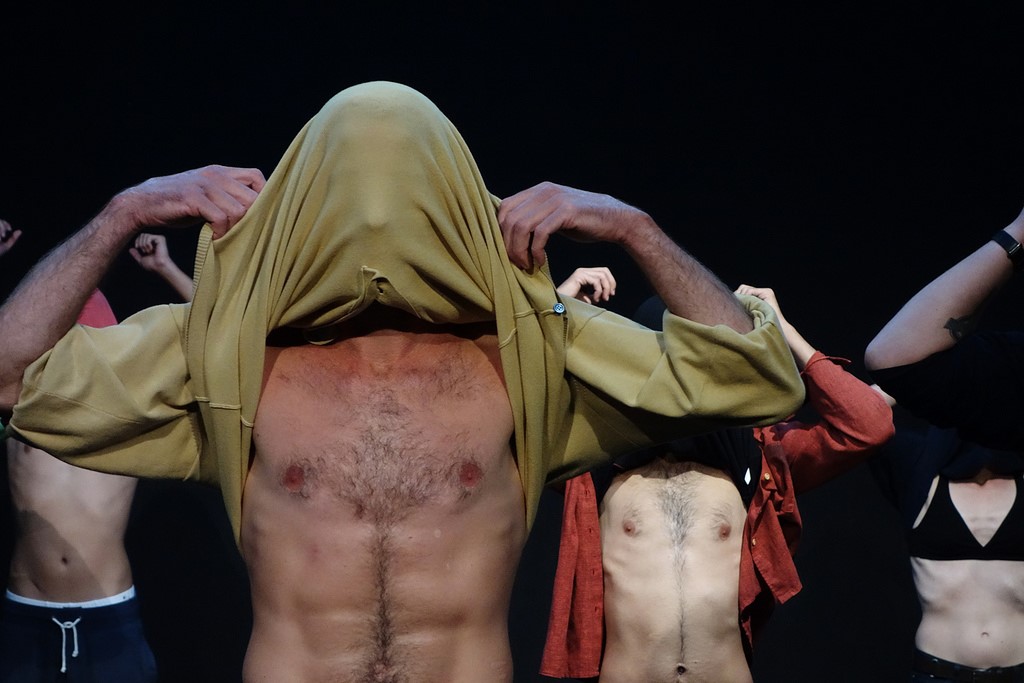

The first section of 8:8 is a silent choreographed piece of physical theatre. The performers sway, turn, lie down, and step into various formations. At times we feel like we’re watching a police lineup of potential criminals or an interpretive freeze of a busy public place. Their timing is refined and the shifts from pose to pose are fluid and organic. It’s still not clear what any of it really means, but there’s something meditative and hypnotic about it all.

The performers finally take seats in a row, mirroring the audience, and speak to us one at a time, in no discernible order, revealing quirky, humorous and very personal facts about their lives and backgrounds. Sometimes, they inform us, they are being honest and sometimes only partially honest. We’re clearly participating in an exercise of judgement and trust. What do we believe? Who do we empathise with? Is this real? The idea of migration also becomes apparent as several of the cast either have foreign accents or reference living abroad or travelling at one time or another. These connections are tenuous though and it’s still not obvious what the real purpose behind the performance is.

Finally, each performer sits unusually close to one audience member, facing us directly, and placing headphones on us. At this point the dynamic changes. Now each audience member is experiencing something unique and secret, as the voice of our performer plays through the headphones, narrating an aspect of their lives to us and only us. While we listen, we are forced to consider our own behaviour. Should we make eye contact with the performer? Smile? Study them? The audio narration again reveals personal information, encouraging us to feel bonded.

When we leave, we are handed information about the inspiration behind 8:8. Swiss Selection Edinburgh (a programme by the Swiss Arts Council) have created this piece as a response to ‘the decision of the Swiss voters to approve automatic expulsion for foreign visitors convicted of crimes.’ This adds a new level of meaning to what we’ve seen, but is also frustrating. The political background isn’t obvious within 8:8 itself, even in hindsight, and the post-show explanation feels odd. The information sheet also suggests the piece is ‘an […] examination of how long it takes for us to form judgements and suspicions.’ This feels, ironically, quite presumptuous about audiences, though. This reviewer had no judgements or suspicions about the performers and their stories. Nevertheless, even if the historical context isn’t clearly tied to 8:8, it is still an interesting experiment in human interaction, audience behaviour, and empathy.