The luckenbooths on Edinburgh’s High Street were a series of locked booths, used by the city’s artisan workers and traders to sell their wares to passing people by day and keep their goods secure by night. The term also came to be used to describe a heart-shaped brooch or a ring, originally given by one sweetheart to another as a symbol of love that was also thought to afford protection from witches.

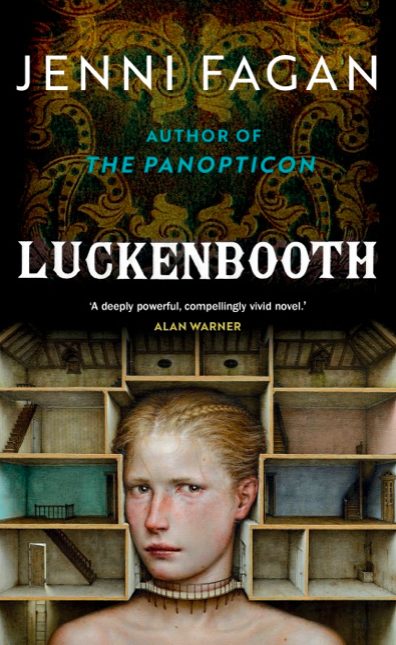

Scottish writer Jenni Fagan beautifully exploits the word’s etymology in her new novel, Luckenbooth. A ten storied tenement nestles in a hard-to-find ‘wynd’ off Edinburgh’s High Street. Fagan gives the reader a window into the lives of nine decades of the inhabitants of 10 Luckenbooth Close from 1910 until the first day of the new millennium. A man cataloguing the bones in the Royal Dick Vet School, a trippy poet, a psychic, a spy, a young woman who sails up the Water Of Leith in a coffin, a miner and a macabre madam defending her territory.

It can be a tricky thing to weave together disparate narratives into a coherent and satisfying whole but Fagan’s characters are bound together not only by their sordid or beautiful predelictions but by the fabric of the building they occupy, the shared creaks and groans, the curse that casts its shadow over all the occupants and the strange permeability of life in a tenement. Along the way Fagan delves into gender, sexual orientation, race, poverty, equality, justice, politics, mental health and climate change and the power of the written word to unite, exploit and orchestrate a world that resoundingly defies description.

And if that weren’t enough, the novel is an incredible love letter to Edinburgh. The city’s layered topography underpins everything: the depraved excesses of those with money enough to fling it around, built on the endless, thankless, cheerless labours of those who don’t.

There’s a deeply defiant streak to Fagan’s writing. She calls out all that is wrong without ever clambering onto a soapbox. Men have called the shots for decades, she notes, though she’s quick to add that there are plenty good men too. Difference – even just getting your “clothes from Tammy Girl, instead of from What Everyone Wants” – makes life harder. The world would be a better place, Ivor the miner realises, if we all got a bit better at working together to fix it. For fear that all sounds a bit too worthy to make for entertaining reading, Fagan is also funny: (Scotland is) “an entire country in an abusive relationship with the weather”.

Alongside the devilish hooves, the slicing knives, the tramadol, tenacious spirits and malevolent fruit cocktails, Luckenbooth is a reminder to appreciate the moment. To dance as if you’re not terrified of what all the tomorrows will bring. It’s a tribute to love and the power of belonging. And it’s a glorious, melancholy, thoughtful, compassionate story that celebrates everyone who doesn’t feel that they fit in. Sometimes, Fagan suggests, the people who are silenced are the ones from whom we most need to hear.