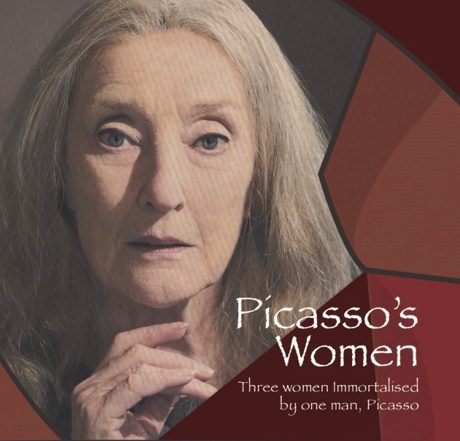

Artist, Pablo Picasso, lived a colourful life. Not just on canvas but in his private life too. He is well-known for his string of mistresses who he often used as artistic muses for his works and in The Fruitmarket Gallery three of them are brought to life in Brian McAvera’s work, Picasso’s Women.

The first of the women to take to the stage and present their monologue on life with Picasso is Fernande Olivier who was a French model for the artist and had a relationship with him for seven years. Judith Paris has an enchanting quality which draws the audience in and holds them transfixed as she builds a picture of a passionate but tempestuous relationship which leaves her, in her latter years, struggling to make ends meet in a one-roomed apartment.

Fernande Olivier exits the stage to be replaced by one of Picasso’s two wives, Olga Khokhlova, a Russian ballerina played by Colette Redgrave who presents a convincing image of a woman who was misunderstood and of a husband who couldn’t cope with change. Due to legal issues Picasso and Khoklova remained married until her death in 1955.

The final woman painted in this artistic showing is Marie-Thérèse Walter, the 17-year-old mistress of Pablo Picasso who is portrayed as a stereotypical ditzy blonde. Kirsten Moore has a hard act to follow after two stunning performances and it is at this point in the play that flaws become more pronounced, most particularly with a very poor attempt at a Spanish accent to represent Picasso.

Given that the play is essentially three solo performances there are some clever theatrical devices employed to give the play a more rounded, holistic feel. Levels are deployed to show the placement of power in each of these relationships. Fernande Olivier is seated before she meets Picasso then elevated to a standing height while she is with him before returning to a seated position to show she has returned to life without him which is far less colourful. Olga Khoklova in contrast, rarely sits, parading round the room showing the power she held over Picasso while Marie-Thérèse Walter is often on the floor perhaps to symbolise her low status as mistress.

It is an informative and thought-provoking look at one (or three) facets of Picasso’s life but that leaves the audience wanting to know more of the untold stories from more of Picasso’s women. Perhaps shorter monologues would allow the inclusion of more of these fascinating stories.

Comments