Co-written by its two stars, Rafaela Elliston and Robbie Martin, Hello Georgie, Goodbye Best is an impressive study in celebrity through one lost weekend in 1971. Football golden boy Georgie Best has gone on a bender and missed training, fuelled by dissatisfaction at the direction of his Manchester United team, but unable to put this across to his manager and mentor Sir Matt Busby. He takes refuge in the Islington flat of actress and sometime lover Sinead Cusack (who is also involved with Peter Sellers) where he gets to escape from the press… for a time at least.

This is a well-chosen time capsule, one in which we can glimpse a certain kind of fame as it balances very precariously on a peak. There’s too much expositional dialogue upfront, but this wears off as the play progresses. Antrim-born Martin carries Best reasonably well, capturing the moody monotone. He feels very static to watch, until actual video footage of the man reminds us just how unanimated a talker Best himself was in those days.

But it’s Elliston as Cusack who injects the dynamics into the piece, a constantly shifting gauge of the piece’s emotional temperature as she tries to mollify, at her own emotional expense, the man-child that is Best. Her frequent costume changes are emblematic in that sense. Best gets to just be himself, the lad, and is adored for it. It’s Cusack who has to change to accommodate. Best is generator of complex drama from simple flaws. Cusack is the more complex individual, but reduced to simple WAG-dom in the eye of onlookers. Elliston and Martin do a good job of capturing the sexual chemistry between the pair. Whatever trouble Best brings, you don’t doubt his bad boy magnetism.

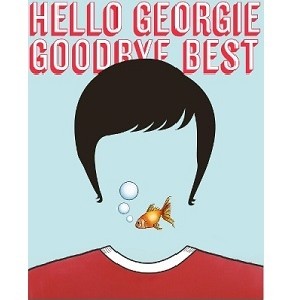

Period detail is nice. Besides the costumes, there’s good use of football commentary and video footage, and as Best and Cusack settle down for some lounge floor loving, Best has a jibe at John Pertwee, the Dr Who that Cusack had been planning to sit down to watch. Cusack’s pet goldfish also act as a useful plot device. They’re used as a surrogate for Busby to help Best open up, and then become vaguely metaphorical as the piece rolls on.

We know, of course, what happened to Best in the end, but his terminal spiral came later. This captures well a young man who, while already exhibiting the traits that undid him, is still at a pinnacle, with time to turn it around, and a young woman, more than a match for George the Man within her flat, but drawn along helplessly by the undertow of George the Legend.

Comments