Like Rome, Edinburgh is built on seven hills. Its most celebrated is surely Calton Hill in the centre of the city. It has long been a popular tourist destination, affording views of the city skyline, down the length of Princes Street to the Pentlands, out over the north side of the city, Leith and its docks, and even the Forth, Fife, and the Ochils beyond. It’s a place of romantic sunsets, midnight trysts, political rallies, May Day celebrations, and art installations.

It is also jam-packed with history associated with Scotland’s pioneer photographers, the city’s first observatory, the National Monument (an abortive attempt at building a replica of the Parthenon in this, the Athens of the North) and the controversial site of a planned Scottish Parliament. What’s more to be said about this volcanic plug? Well, it turns out, plenty.

Few cities can boast such a magnificent topographical feature (well, Paris, Rio, Rome). Kirsten Carter McKee takes a wide range in terms of history, geology, and biology. She even covers the hidden private gardens that back onto Royal, Regent, and Carlton Terraces and the Third New Town that was never built.

The most dominant feature on the hill is the national folly set of imposing stone columns. The builders ran out of money and the entire Greek temple, also never built. The hill and its plethora of commemorative structures were “conscious efforts to promote the monarchy and the British state after the French Revolution and during the Napoleonic wars,” writes McKee.

Calton Hill is almost a dreamscape with its views over the city and surrounding countryside and assorted domes and columns. It is disappointing that the writer does not use more poetic language in describing the historical ecology of the hill. Yes, she is an academic and architectural historian, but the book too often reads like an indigestible PhD thesis.

Current socio-political dilemmas are also absent. Edinburgh prides itself in its special UNESCO status awarded for its architectural splendours. It is this very special architecture and topography that attracts droves of tourists throughout the year. And while these millions of marching feet threaten the infrastructure of the city the political establishment seems powerless to intervene. A tourist tax and building of endless boutique hotels have become a real controversy.

Take the disastrous dilemma of the former Royal High School at the South East base of Calton Hill. Adam inspired, lauded with praise for its perfect symmetry, as much a symbol of the Enlightenment and Athens of the North as the National Monument on top of the hill – the School sits as a neglected reproach, largely unused, threatened by the elements, with weeds growing in its gables, its lower reaches littered with broken glass. Recently a developer wanted to turn the former school into a luxury hotel – retaining most of the building but adding to ugly glass wings. The plan was met with appalled cries of desecration.

The rise and fall of the RHS is inextricably linked to Scottish Home Rule, devolution and independence. The RHS has become a divisive symbol as much of Scottish intransigence and prevarication as anything else. The building was long seen as a natural Scottish parliament. In the 1970s it was fitted out with a debating chamber replete with funky Starship Enterprise-style seating for the speaker. And in the 90s there was an independence vigil based at the gate.

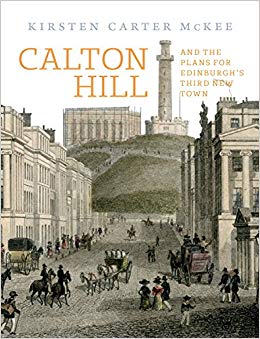

Site of Beltane festivities, notorious cruising ground, tourist mecca, and now home to re-energised Collective Gallery – McKee is less good at capturing the more zeitgeisty aspects of Edinburgh’s “city hill”. But there can be no complaint about the glorious illustrations in the book that showcase everything from early architects’ plans to the work of pioneering photographers Hill and Adamson, to Thomas Begbie’s famous photograph taken in 1887 of washerwoman drying bedsheets in the south facing slopes, and the proposed and unrealised 1909 revamp of the National Monument, modestly titled Open Air Valhalla.