We’ve only recently seen Michael Fassbender scorch up the screen as the Thane of Cawdor in Justin Kurzel’s adaptation of the Scottish play, yet Angus Macfadyen (Braveheart) gives us Bard botherers another take on the classic, and it could not be more different.

Set mostly within the confines of a sleek black convertible cruising the graffitied ghettos of what appears to be New York, Macbeth Unhinged is an ambitious and defiantly experimental take on the familiar tale, shot in stark black and white and filled with striking imagery – the opening dialogue with a wounded captain, ‘he fixed his head on our battlements!’ – is accompanied with the sight of said head as a grisly hood ornament.

Perhaps the standout moment is the famous ‘dagger’ soliloquy, unusually presented with Lady Macbeth (an icy, seductive Taylor Roberts) present. Macbeth addresses her, caressing her face, as much as the length of steel in his hand; implying that she is not merely the catalyst for his actions, but a potent weapon in her own right. It’s hugely impressive.

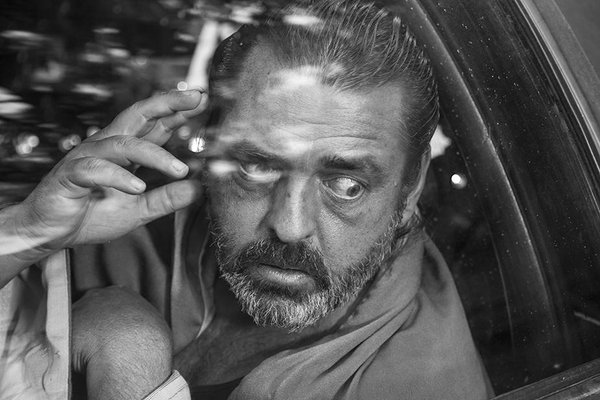

Macfadyen, in the confines of his vehicle, is a caged animal. An imposing, bulky figure, at times he resembles a haunted, bristly Orson Welles; fittingly for a piece of work with such a film noir influence. During other scenes, with hair tied back and wearing a kimono-like robe, he looks startlingly like Toshiro Mifune in Akira Kurosawa’s sublime adaptation, Throne of Blood.

However, the claustrophobic surroundings stunt the dramatic potential, and Macfadyen compensates with various techniques such as super-impositions, characters appearing and disappearing (such as the three witches, almost omnipresent here as a winking Greek chorus), and an exaggerated grotesquerie in the performances. These deliberately obfuscatory touches, while undeniably stylish and evidence of commendable ambition, force an already challenging adaptation into the realms of impenetrability.

Be warned, those who are coming to this film without any prior knowledge of the text are destined to be baffled, and then ultimately bored. Macfadyen clearly knows the play on an almost anatomical level, and has adapted it in a way that those with enough knowledge may peer through the murk and glimpse some clarity while newcomers will be groping in the dark for an exit. The deaths of several characters are confusingly presented, particularly Duncan’s; and the level of abstraction saps those scenes of the power of Macbeth’s betrayal.

Overall, it must be said that Macbeth Unhinged is a commendable failure. A shame, as the originality and sense of adventure on show can only be admired. Those fully versed in the play could potentially glean some satisfaction; Banquo’s ghostly appearance is winningly creepy; and a nervy, skittering, genre-hopping score ably accompanies Macbeth’s disintegrating mental state. It simply needed more clarity in the story-telling to complement the visuals.

Macbeth Unhinged

[Rating: 2/5] Ambitious, experimental, but ultimately impenetrable new version of Shakespeare's classic tragedy.

Reading time: 2 mins