The Traverse‘s artistic director Orla O’Loughlin is certainly going out with a bang. Her final production with the theatre, Mouthpiece, is a staggeringly clever and skilfully executed exploration of social inequality, exploitation and appropriation.

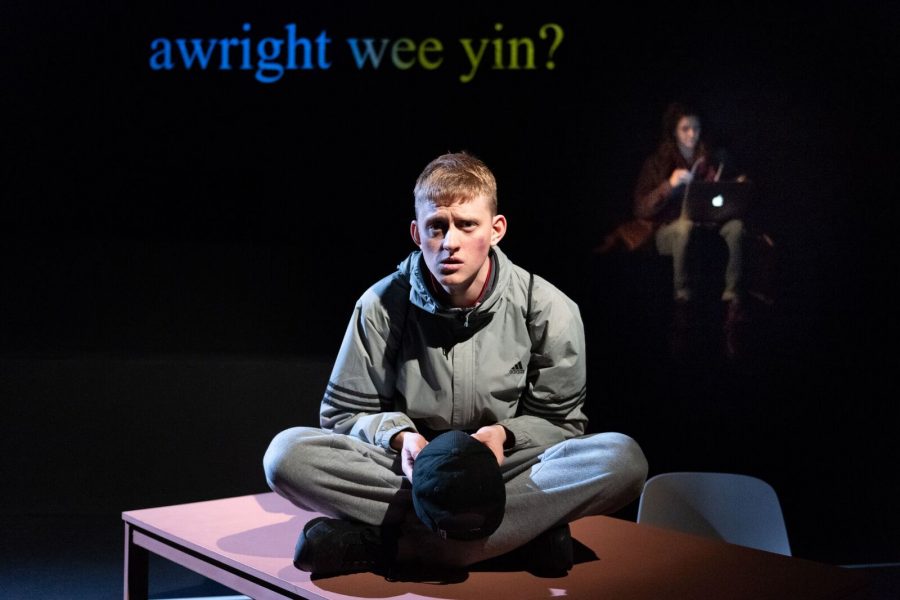

After 16-year-old Declan (Lorn Macdonald) intercepts and prevents the suicide attempt of forty-something playwright, Libby (Neve McIntosh) on Salisbury Crags, an unlikely bond develops between the pair. Intrigued by Declan’s artistic talent, the lonely Libby pursues a friendship with him, and soon finds inspiration for her own writing in his gritty accounts of his impoverished life. His formative experiences of inescapable domestic abuse, addiction-based tragedy and mental health problems are seemingly far removed from her own middle class, New Town existence. Yet, his unhappiness, disillusionment and isolation feel familiar to her. She feels she can help improve his life by encouraging him to embrace the arts, while he can improve hers by providing the material for her next play. Libby thinks she is giving “a voice to the voiceless”, but it soon becomes clear how well-intentioned class tourism like hers serves to perpetuate the restrictive barriers that oppress and harm people like Declan. The dualities of Edinburgh, the city of Jekyll and Hyde, are illustrated with stark precision. Exorbitantly wealthy residents and those living in the many pockets of multiple deprivation both claim the city as their own, but they inhabit incompatible, unrecognisably different Edinburghs.

Mouthpiece is a highly self-reflexive piece of theatre. Just as you’re developing the uneasy feeling that the play is itself an example of the patronising poverty porn it seeks to condemn, it is made clear that writer Kieran Hurley is intentionally laying bare his own personal conflicts about social class and identity – acknowledging his own potential for hypocrisy as a hugely successful writer presenting a project such as this. Hurley’s keen self-awareness and capacity for reflection is what sets this play apart – the humility and honesty of Mouthpiece are arresting. The Brechtian elements of the staging and the performance, such as the white frame around the stage and Libby’s secondary role as a sort of Greek chorus – providing metacommentary at key points in the drama – add to the authenticity and credibility of Hurley’s message. The wit and humour of the script add to the play’s heart and irreverent charm.

As Declan, MacDonald is an absolute force of nature; his performance is phenomenal. Even the moments in the play when his character threatens to become a reductive working class stereotype are saved by MacDonald’s perceptive, convincing and utterly compelling acting. McIntosh gives a similarly accomplished turn as Libby. Despite the character’s thoughtlessness and obliviousness to her own privilege, McIntosh ensures Libby is never a wholly vilifiable individual. Her flaws are human; her unhappiness is genuine. Therefore, she elicits a degree of sympathy. McIntosh truly shines during a scathing tirade about the superficiality of the bourgeois world of writing and the damaging impact it can have on writers’ sense of identity and emotional well-being.

The timeliness of the play is indisputable. Discussions about social class inequality, including in terms of accessibility and representation in the arts, have been brought to the fore by the likes of writer Darren McGarvey, whose polemic Poverty Safari won this year’s Orwell Prize. Provocative, daring and completely riveting, Mouthpiece proves yet again that the Traverse is Scotland’s leading light when it comes to important and exciting new writing.