In its subject matter, Ross Ericson‘s solo piece about an end-of-his-tether middle-aged comedian is oddly daring. The Fringe pats itself on the back for its radical, dissenting voices, by which is usually meant the likes of Pussy Riot, who, while controversial back home, no self-respecting Fringe-goer will have any issue with. But this, in which Ericson’s character rants frustratedly about identity politics, or, to use the nomenclature of the times, turns “gammon”, could give some people a funny turn. There’s a genuine frisson to hear him say things which less than a decade ago wouldn’t have batted any eyelid, but now, to some, would render him like a character from 1930s Germany. It certainly challenges your thinking, whatever your politics. Is what he’s saying actually racist/transphobic/misogynist? Are we so sure progressive politics is always right? And if so, why is this middle-of-the-road chap being thrown out with the bathwater? True to what Ericson said in interview, he doesn’t answer these questions, but he does dare to pose them.

Unfortunately, the juiciness of the subject matter does not yet have the right structure surrounding it. There are three somewhat competing framing devices. The first is the Book of Job, in which God tests a man’s faith by heaping suffering on him, intoned by a voice-from-beyond with added jokes. The second is snippets from a TV show on which Ericson’s comedian character has had a meltdown after hearing something he didn’t agree with from a feminist commentator. The third is a well-chosen soundtrack of music from the comedian’s youth, to which he reminisces about raves and the good old days. That’s a lot of threads to weave together and as yet, they’re hanging somewhat loose, and leaving the body of the piece exposed as unrestrained ranting.

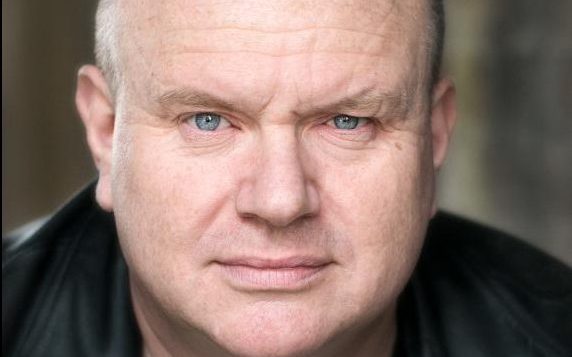

Our protagonist is holed-up in a hotel room hiding from the police investigation and social media furore his TV outburst caused. It’s there he breaks the fourth wall to tell us of his grievances and frustrations. With his white shirt, bald head and food-friendly waistline, there’s something of Al Murray, the Pub Landlord, about him.

Some lines play like stand-up – the character is a comedian, after all – but they don’t land like stand-up, and not through any fault of Ericson’s. Part of it is the lack of intimacy in the container-like Blue Room in George Street, part of it is the expectations and constrictions of a theatre audience. One suspects it might take a different venue and audience for the ranting to truly hit.

There’s some interesting, non-obvious points made. In his tirade about class, he questions how this got retooled to fit modern oppression culture, and what basis it often has in reality, taking a swipe at ex-Globe director Emma Rice on the way.

His daughter is half-Chinese and this also throws up some interesting tensions. For her, the white part of her heritage – his part – carries shame. Yet, in one of the more effective flashback sequences he recalls the awakening of seeing Steel Pulse at the Rock Against Racism concert – “we went for the music, we left with the politics” – and wonders what part of his own understanding, and joy in multi-cultural harmony, he must now apologise and feel shame for.

Too often though, the character and his life haven’t been sculpted enough and tend to the generic. The unnamed seaside town he calls home feels quite template, as does his 1980s rave experience. He offers up opinions on everything too, and the topics aren’t all developed to the same level. Fitting that wide-ranging subject matter with the peaks and troughs created by the developing storyline and framing structure would be very effective if it could be pulled off, but it’s not there yet.

There is one perfectly timed moment where he delivers an emotional gutpunch just as the Smiths’ Last Night I Dreamed Somebody Loved Me kicks into life (if you know the song, you’ll know which bit). It sends a shiver down the spine in this form, but if the dynamics of the build-up can be better, it could be even more effective.

Somewhere in all this is a fascinating character study which offers up strong challenges to the prevailing, and fashionable, consensus. If it hits all the points it wants to, it could be barnstorming. There’s still some work to be done, though.