Billed as an ‘unreliable retelling of Moby Dick’, The Wild Unfeeling World is an intimate show, both in terms of its venue and the brittle feelings it explores. Performing in a wood-lined room reminiscent of a ship’s hold, Casey Jay Andrews lays bare her thoughts about the delicacy of human connections – and the crippling fear that asking for help will unduly burden those we reach out to. In truth it owes very little to Herman Melville: there are some amusing references to events and characters from his novel, but the parallels are too superficial to bear much scrutiny. That doesn’t matter though. This story stands up on its own.

At its heart it’s a tale of compassion, and of how other people’s thoughtfulness can lend you the strength to carry on. At the start of the play, protagonist Dylan’s in a bind: she’s been mugged, she’s without either money or phone, her car’s broken down and she’s just been thrown out of her millennial flat-share. Driven by a mix of nostalgia and sheer cussed determination, she decides to walk – walk! – from Heathrow Airport to the London Aquarium at Westminster; there are setbacks along the way, but she finds that both acquaintances and strangers are kinder than she’d bargained for. It’s a simple and big-hearted narrative, but it carries some heavyweight messages about the power of sharing your problems, and about being patient with others when they share their problems with you.

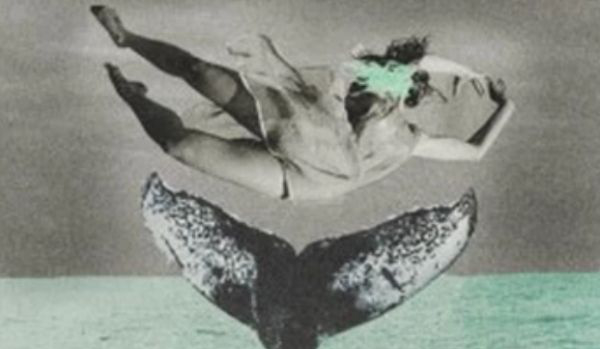

Alongside this very real and very human story runs a second, fantastical tale – involving a cat called Ahab and his posse of felines, who are cruising down the Thames in search of vengeance against Dylan (or, more specifically, her car). It does take a mental leap to accept the whimsy of this story: at first I assumed the cats were on a river-bus, when in fact it turns out that they’re sailing in their very own (pea-green?) boat. If you think too hard about it you might question what this sub-plot actually adds to the story, but it’s a cute and quirky way to forge a link with Moby Dick, and it sets the scene for a fast-paced conclusion as Ahab and Dylan converge on Westminster Bridge.

Andrews’ style of storytelling suits both the playfulness of her narrative, and the fragility of her protagonist. The line between actor and character is a sketchy one; sometimes she highlights her own creative thought process, sometimes she gives us a sneaky hint of what’s about to come. Reinforcing the sense of a journey shared, notes and sketches are pinned to the wooden wall – a map here, a word or a sentence there, an idea to speculate on and listen out for. If you know London, you’ll enjoy how rooted the story is in familiar places, and it’s tied to a real-life event as well… something you’ll probably remember, which you’ll kick yourself for not having guessed would be featured at the end of the tale.

The Wild Unfeeling World isn’t as finely-burnished as some other work: in places it’s rough, maybe even messy, and sometimes it’s expository to the point of defiance. But that eccentricity is what gives it personality, and the personality is what gives it both significance and heart. It’s a reminder of how much it matters to communicate – and how the times when it’s hardest are when it matters most of all. And it’s a story of survival, even in the teeth of a storm.