Ostensibly one of the longest running shoegaze bands out there, The Veldt formed back in the late 80s and flirted with mainstream success without ever actually going the whole hog. Despite having supported bands like The Jesus and Mary Chain (in the UK) and Cocteau Twins (in the US), as well as having shared the stage with such heavyweights as Pixies, Manic Street Preachers and Echo & The Bunnymen, The Veldt never quite achieved the same status as those household names, nor the success that dedicated fans of their cult album Afrodisiac will insist they deserve.

Why? More than anything, it appears to be down to their skin colour. At a time when experimental rock and in particular, the shoegaze genre, seemed to be the domain of white kids and white kids alone, The Veldt were told that they “didn’t sound right” and that they were “difficult” to work with. Frustrated with the intransigence of the music industry, founding twin brothers Danny and Daniel Chavis shelved the project in 1998, only emerging in the mid 2000s under the moniker Apollo Heights to release the thinly-veiled jibe White Music for Black People.

Now, The Veldt are back with another EP released this March and a full album in the pipeline. Predictably, much of the chatter surrounding their return has focused, once again, on their skin colour, with The Guardian surmising that the world might finally be ready for a black shoegaze band and Vice praising them for their dogged pursuit of racially inclusive music. That’s all well and good, but it seems (this article included) that more time is spent talking about The Veldt’s struggle than their songs… so how do they sound?

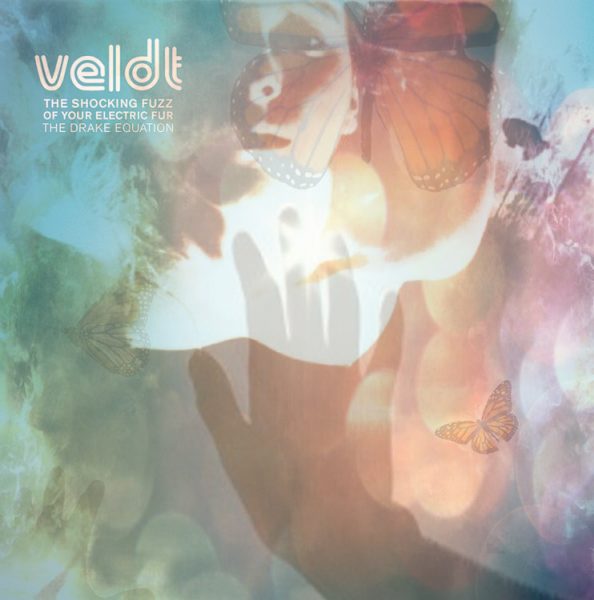

The Shocking Fuzz of Your Electric Fur is an immediately refreshing mix of styles, with elements of shoegaze and electronica mixing with blues and soul, the swelling melodies allowed to soar free but ultimately reined in by the vocals of Daniel. It’s perhaps this unpigeonholeability which made them unpalatable to the big dogs of the music scene back in the 90s, but equally as attractive to their fan base, and there’s no doubt that aficionados of musical experimentation will find much to like about the new EP.

For all that innovation, however, the songs do share a sort of uniformity that serves to detract from their overall impact. The repetitive back beat is almost identical on the first, third and fifth tracks, for example, making them slightly difficult to differentiate. The resulting effect is a soothing, immersive experience in which song durations slip past without much in the way of milestones, so that by the record’s end, the listener emerges from a trippy fugue unsure of how many minutes (or hours) have elapsed in the process… which is perhaps exactly what this kind of music is intended to induce.

All in all, The Veldt’s history and their perseverance in remaining true to their own ethos does lend a layer of meaning and credibility to their work – but it shouldn’t define it. Rather than being labelled as a pioneering black shoegaze band, they should be recognised as enduring proponents of the genre who successfully blur its lines and bring in very welcome alternative influences. Hopefully, 2017 will acknowledge this latest release for its ample musical merit and see The Veldt begin to get the recognition they deserve.