There’s a tendency to see a line of demarcation between science and art; one is cerebral the other imaginative, one empirical and rational the other creative and inspired. But the collaborators of ASCUS – which is part acronym (Art, Science, Collaborative), part pun (Ask Us), as well as the name of a spore which represents their desire to generate ideas, clearly feel it’s a false division and in this exhibition they’ve developed artworks from a cross fertilisation of the two disciplines.

Taking over an empty shop in the St James’ Centre, this small exhibition takes a mixture of approaches to enlighten different scientific subjects and open them up to the public. Artist Mark Eischeid gave us a tour and helped explain the science, art and philosophy of ASCUS.

How does the collaboration work between the artist and scientists?

The intention here was that the artists and scientists applied together for a grant to work on this exhibition. So rather than a case of ‘you do this and I’ll do that’ it was meant to be a parallel collaboration. The project ideas were thought up together and so, for example, in the work ‘How Steep Is Now’ by artists Liz Adamson and Graeme Todd and scientist Mark Huxham – based around a series of interviews on climate change with people from Scotland, Kenya and Japan – all of them were already working with the subject of climate change, so there was an affinity between them even before the project, so it was truly a collaboration of ideas.

In the past, particularly at the time of the Enlightenment, art and science were much closer. Is ASCUS an attempt to go back to that time and bridge that gap?

I think you’d get different opinions regarding that question from those involved. Certainly there is a gap and we’re trying to illustrate that there’s an opportunity here, with similar methods of enquiry, to combine efforts and to try to figure out new things through that collaboration. There’s no doubt that there is a gap between the two, but a lot of people we talk to realise it’s a space that can be occupied by this sort of work.

Art has always been fascinated with science. There’s a lot of organisations around the world doing similar things to ASCUS. There’s also been a push for public engagement in science. A lot of science grants are given with the stipulation that part of the money will be spent on public engagement. We received funding from Edinburgh Beltane – Beacon for Public Engagement to execute this project.

Artists have always been very democratic in how they get inspiration, and it’s easier for us to convince an artist about this type of collaboration. It takes a litle more discussion to bring a scientist around to the benefits. Scientists are obviously evaluated differently, with peer review and published papers, so working with artists doesn’t have immediately recognisable benefits. There’s a huge opportunity for journals and conferences that focus on art and science to develop this kind of work.

None of the the works in the exhibition are representational art so is the idea to inspire questioning from the patrons in order to open them up to the science involved?

I think that’s true. One of the tricky parts to both areas, but particularly science, is that there are some very detailed, technical aspects to it which are difficult to communicate quickly, but there are some basic fundamental concepts behind them, and that’s where the artist can come in and communicate those basic ideas that don’t require a science degree to understand. A good example is Happi Genetics, a work from Mar Carmena and Sasha Kaganski from the Wellcome Trust Centre for Cell Biology at University of Edinburgh and artist Shaeron Averbuch. Their project was less about the works on the wall – sculptures and images representing cells and cell division – than a series of workshops with primary school children in Edinburgh demonstrating cell division through craft and dance. The cell sculptures on the wall were made by the children as part of the project.

Mar, Sasha and Shaeron had been working on this project before this exhibition and they plan to continue, using the works here, with future workshops.

Was the unusual choice of venue in the St James’ Centre borne out of the ideas of access and communication or was it a choice dictated by finance?

No, it was definitely by design, but fortunately it’s worked out financially as well, and the St James’ Centre have been great at supplying us with equipment and facilities. The original intention was to give access to anyone and everyone. We initally expected to find somewhere more peripheral in the city, so this has been a great bonus to what we’re trying to achieve.

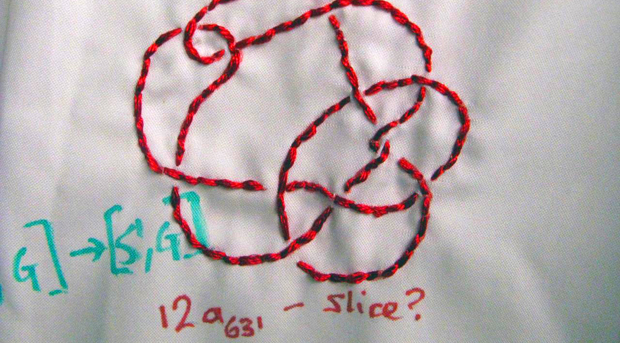

The first work that visitors to the exhibitions will see, even before entering the exhibition, is The Mathematician’s Shirts: a display consisting of a series of shirts cut and tied into knots and scrawled with complex formulas created by two mathematicians Julia Collins and Madeline Shepherd who is also an artist.

The formulas and calculations on the shirts are representations of things that literally have been or might appear on a blackboard, so on some of the shirts you see formulas embroidered or stitched on, some of which represent work from the PHD thesis of one of the exhibiting mathematicians on knots, which is further represented by the cut and knotted shirts also part of the display.

Obvious question but why shirts?

First, it’s an easily available and mouldable, sculptural material with something three dimensional about it. The collaborators solicited shirts from fellow mathematicians and so in some cases they’ve literally taken the shirts off their backs. It was also an opportunity to be quite playful, and as everyone knew that the exhibition would be in a public space, particularly a shopping mall, we thought these would be especially appropriate.

Are there any plans to tour the exhibition?

There are no plans yet, but we have looked at taking the work to the Edinburgh Science Festival, and some of the groups involved have discussed taking the works to other science festivals and events around the country. We’re very fortunate to be in Edinburgh and Scotland which provides fertile ground for both disciplines to develop and has certainly been important in creating the potential for this project.