‘A Jacobite in the dress of a Glasgow lawyer’ is the self-description of Willie McRae; SNP bigwig, anti-nuclear campaigner and the man who was found dead in his car with a bullet in the back of his head on a remote Highland road 34 years ago. The gun responsible was flung far away from the car into a burn; there were papers missing from his effects. The assumption of suicide is shaky to say the least.

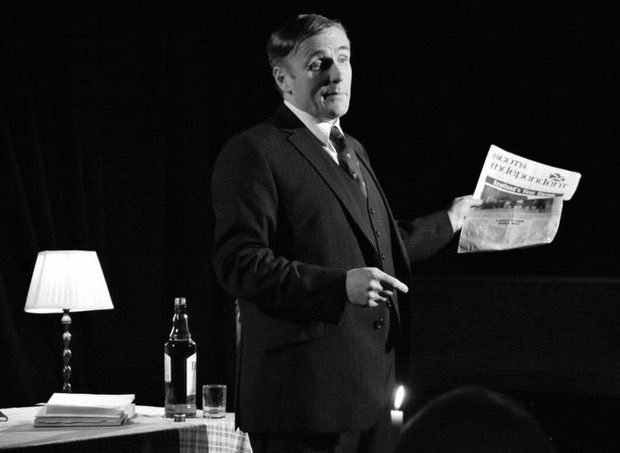

Made by and starring Andy Paterson, 3,000 Trees: The Death of Mr William McRae gives us a flavour of this enigmatic man and the mysterious circumstances that surround his death, as well as a glimpse into the reawakening of nationalist sentiment in the 70s that brought us to where we are now. It’s both a character study and a cultural one.

McRae is of a generation, born in the 20s, that’s now beginning to slip out of contemporary memory. That background gives rise to two of the inner conflicts that shaped his later life and thus indirectly may have led to his death.

The first is his personal complicity in the dying embers of Empire. An officer in the Navy, he served the United Kingdom – the state he ultimately wished to disunite – at the end of colonial rule in India. McRae mulls this over. Yes, he served the state, like so many did, yet it led him in a different direction. Indian emancipation, which he supported, and the Indians’ willingness to take up arms, came to inform his approach to Scotland’s own independence movement. There’s some choice, un-PC language here, which jars on the ears now, but helps place us into that context.

The second is his rumoured homosexuality. The play deals with this delicately, not making him formally out himself, but allowing us to see the struggle in his head. He’s no John Inman or Larry Grayson, he says. He’s a ‘man’s man’. And his navy career was not one of Village People stereotype; it was the pomp and brotherhood that did it for him. Eventually, he rediscovers that same sense of brotherhood, not to mention strong, young Celtic manhood, during his flirtations with fringe independence movement Siol nan Gaidheal. Barred by the SNP as extremists, we know why McRae himself is drawn to the movement – and we’re not being asked to condemn him for it.

All the time we’re being guided to an impression of McCrae as an outsider, at odds with convention. This feeds his paranoia – there’s definitely an air of the conspiracy theorist about him. But you can’t dispel the notion that he may have been onto something. ‘I’m no fool,’ he claims and that’s no delusion; it’s not paranoia if they really are after you. With his opposition to the nuclear lobby and disdain for both British and Scottish establishments, he definitely had enough enemies.

Paterson is commanding in the role, although actually comes across much smarter and mentally together than the scruffy alcoholic we’re being told people think McRae is. Measured and sure with his speech, and with a keen intellect, it’s clear why people wouldn’t want him poking round their business. Political machinations that could seem dry are succinctly handled. The Mullwharchar Inquiry into nuclear waste disposal was probably interminable and dull as ditchwater, but McRae’s engagement with the subject wins us round. He comes across as a lively rhetoricist.