Somewhere deep within Coldplay there’s an interesting band trying to get out. Brian Eno knew it, and did his best to coax it out of them on Viva La Vida; there have been sporadic glimpses of it before and since. Yes, they’re irredeemably guilty of the blandification of 21st century rock. No amnesty for that. But they’ve also displayed more musical breadth than their copyists, and occasionally appear to have the inclination to produce a genuine piece of art. Right here, for instance, on the sprawling, genre-promiscuous Everyday Life.

But they just can’t help themselves. They always have one eye on the million-seller, the radio hit, the stadium arm-waver. Any edge they accidentally display is instantly sanded off, any musical brew that looks too potent is watered down for fear it may leave a nasty aftertaste. And so with this eighth album – for every thrilling surge of brass or middle eastern melody, there’s a dozen drippy lyrics like ‘Daddy, are you out there? / Daddy, why’d you run away? / Daddy, are you okay?’ aimed squarely at the lowest common denominator.

It’s not even as if this instinctive reversion to safeness is done purely to appease Parlophone bosses. No doubt they have execs breathing down their neck fretting over the share price, but they’re obviously indulged enough to be allowed this two part Lonely Planet guide of globe-trotting musical diversions, rather than, say, ten more Fix Yous. They could, just once, get truly adventurous. But no, Coldplay’s tameness is self-inflicted. The careerism is in-built. They like being Coldplay plc; it’s not forced on them from above against the will of their muses. When faced with the choice of an extra couple of noughts on the P&L or a notch on the artistic credibility scale, they always plump for the former.

Their whole approach is exemplified by the double A-side which heralded this album. First you get the ear-grabbing Arabesque, with its filthy jazz sax break and a North African groove so insistent you could forgive Chris Martin the pretension of singing en français. Then you get the cheesy global village rhythms and woo-woohing of Orphans, because that’s the one that’ll get the arena jumping. They give with one hand, they take with the other.

Everywhere they flatter to deceive. The album opens with Sunrise, two and a half minutes of rich, evocative chamber music, put together with long-term arranger Davide Rossi. We’re not talking lame #instawedding string quartet love song either, we’re talking the opening credits to something moody and Central European. But as soon as the thought passes your mind, ‘ey up, they could be on to summat here,’ it dissolves with the arrival of Church, a song you can imagine Jeremy Vine rhapsodising about, all skippy drumbeats and ‘when I’m with you I’m walking on air / watching you sleeping there’. Chris, mate.

And so on through the album – the ambitious sat next to the trite. They’ve purloined an impressive set of genres and styles, but it’s all been done so self-consciously as to be a turn-off. It’s neither a White Album stream of consciousness, nor the result of immersion in one specific musical culture to create, say, their ‘Malian’ album, a la Damon Albarn. It’s a ragbag of carefully selected cultural signifiers that gives them a patina of experimentalism.

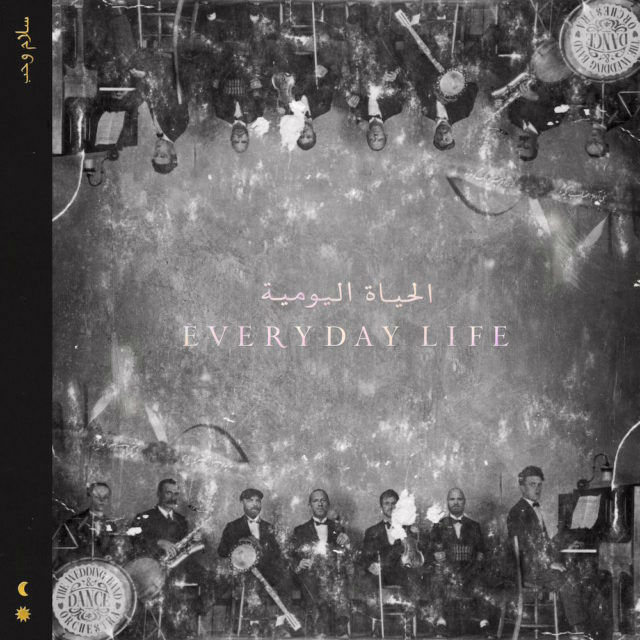

The budget means huge attention to detail – artfully constructed dialogue snippets or ambient sound samples, and the guest musicians are top notch – Femi Kuti and family, for instance, although one suspects even the lesser known names are outstanding artists in their own right. It’s all for show, though, and stylistically not very coherent. Where in the world are they? The cover photo suggests New Orleans jazz band, but Arabesque says Francophone Africa, بنی آدم (Children of Adam) is based on a Persian poem, and… well…

Cultural appropriation is a contentious concept. Apply it too stringently and you render most of popular music off limits. But if ever there were a cut-and-dried case for a clampdown, it is this whitest of white bands trying their hand at gospel. BrokEn does indeed make you holler ‘Oh Lord!’, but not for the reason Chris Martin intends.

That said, the globe-trotting does result in some beautiful moments. The guitar work on Èkó and Old Friends is gorgeous. (Again, please close your ears to the lyrics: ‘In Africa the rivers are perfectly deep and beautifully wide’). When I Need A Friend‘s male voice choir is restorative, and the stately classical intro to the aforementioned بنی آدم is pleasingly unlike listening to a Coldplay album.

The Richie Havens-esque 60s protest strumalong Guns is a tad obvious, but not wholly unpleasant. You’d even (maybe) settle for the croonerish Billy Joel meets Michael Bublé of Cry Cry Cry, if they’d fully committed to it, and it wasn’t just another dilletantish style switch. They haven’t stuck to anything on this album.

Coldplay 2019 are not the ‘bedwetters’ Alan McGee famously accused them of being 20 years ago, but nor are they the charismatic polymaths this album is constructed to make them appear. Crack the veneer – a beautiful and expensive one – and it’s still full of musical and lyrical platitudes. Everyday Life crosses curious musical avenues, but there’s a reason the streaming algorithm takes you to Bastille afterwards and not Tinariwen.