Dead White Anarchists is something of a throwback to when political theatre meant the exploration of grand universal ideas rather than hyper-personal testimony. Delivered by spoken word artist Paul Case in ranty, agitprop style, it makes for a welcome revival of an out-of-fashion form.

The one man show, reworked from its Fringe incarnation under the guidance of director Emily Ingram, introduces us to the real life story of Émile Henry, a young anarchist in 1890s Paris. Henry has inherited a radical streak from his Communard parents and has had it stoked by contemporaries in the run-down arrondissements in which he lives. As fellow revolutionaries get arrested and executed, his attitude hardens, ultimately leading to an act of terrorism of his own. If nothing else, it’s a good history lesson and successful evocation of fin de siècle France.

But it’s not simply history. Case has his own experiences of activism and squat parties and has brought that to bear on proceedings. In a dream sequence, a drunken Henry, who by now has escaped from Paris to London, finds himself wandering into a drug-fueled rave where he meets anarchists and hedonists of the modern day, and grows to understand where all this talk of anarchy might lead. As an audience, it takes a while to reorient ourselves to what’s actually happening, but that sense of disorientation fits the tone.

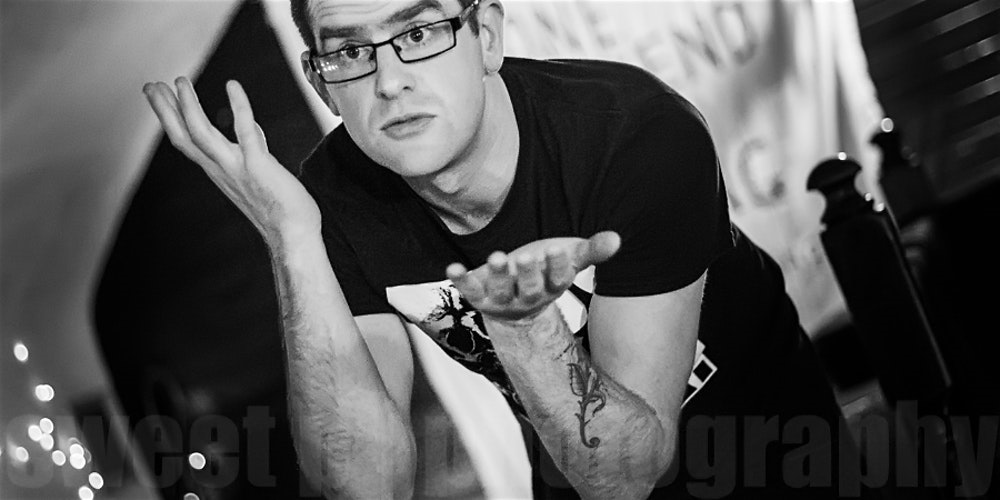

This evening at least, Case has gone for a Two-Tone look – pork pie hat, B&W t-shirt (of punk band DOA), turned up jeans and Doc Martens – perhaps another reason the play feels like a return to the radical 80s. The hat is more than decorative though. Case tugs at it tensely or carries it confidently as the text requires. As his sole prop, it also stands-in for people, or doubles as the bomb he’s fearfully clutching to himself. Simple staging that suits the storytelling form.

The piece doesn’t flinch from Henry’s nihilism. His disregard for human life is all the more shocking for having been intellectualised. This isn’t a man misguided by mental illness or radicalised by religion. He genuinely and callously wants to see the bourgeoisie dead. All of them. It’s here that the power of Case’s warehouse rave time-shift becomes apparent. The effect has been to blur the 130 year timespan and relocate this long dead Parisian in our imagination. He’s no longer a distant figure. He’s any young radical with more conviction than compassion.

It also means that Dead White Anarchists is a political piece without clear agenda. One of the standout lines (if correctly remembered) is about activism with the “posturing boiled off and distilled into violent action”. Case spits it like a man who’s probably seen his fair share of ineffectual political posturing, and yet his piece is no apology for violent action either. There’s no doubt 1890s Parisian society was failing people, as has nearly every society since, but while Dead White Anarchists makes the superficial appeal of anarchism clear, it does not suggest that it’s the solution.