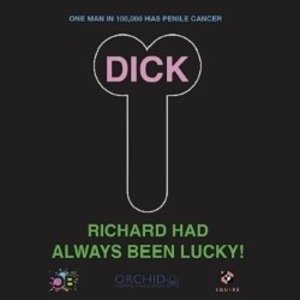

A show about male cancer, or to be precise, a partial penectomy (surgical amputation of the penis), is not necessarily an immediate first choice for a person’s Fringe diary. Described as a comic tragedy of hope over death, this is more a serious piece of theatre, serving to build awareness for a little-known male cancer, which affects one man in every 100,000. There are elements of humour in the play but it’s not really a laughing matter.

Richard Stamp, Stompy to his friends, and not to be confused with our very own Richard Stamp, is living the good life, working in South Korea for the British Council. Finding a pea-sized lump at the bottom of his penis, he chooses to do what most men would do, which is to initially self-treat it and then ignore it.

After two months, he finally seeks medical intervention at a private clinic in Adelaide, with the shocking diagnosis that it’s penis cancer, it’s stage three or four, and there’s only one thing for it, amputation.

Seeking a second opinion, this time in London at St. George’s Hospital Tooting, which luckily for him is the number one hospital in Europe for penile cancer, his initial diagnosis is confirmed, with the need for a partial penectomy. And this October, or as he likes to call it, Cocktober, with the help of modern technology and science, will see him having an operation to rebuild his manhood, with the help of skin from his right forearm.

With an original soundtrack by Ben Raine, and written by James Chaplin, the script is at times clunky and doesn’t always flow smoothly but Stamp does an admirable job of engaging the audience with his honesty and the need to tell his story and be the face of penile cancer.

Dates feature heavily, diarising the journey from a carefree life on holiday in Brazil in November 2016, pictured naked with his manhood, to April 2018, the amputation, to August 2022, him performing at the Fringe, smashing taboos and telling his ‘cocktale’.

The medical journey unfolds with the use of film, animation, and music, and while the many penile references (think bananas and palm trees made of dicks) are there to inject comedy, light relief, and to reinforce the storyline, their use is almost too blatant. What is more powerful is the x-rays and images of his operation and the stories of his time in the urology ward that pose the shocking reality and harshness of Stamp’s diagnosis. The finale, which, without giving too many spoilers, features what we’re led to believe is Stamp’s amputated member, is powerful.

This is no cock-and-bull story but more an honest, autobiographical ‘cocktale’ of one man’s plight to raise awareness for a little-talked-about male cancer. Whilst it needs some polish, it does a good job of getting a serious message across.

Comments