In Iona Lee’s first pamphlet, several poems are about spirituality. The first poem ends with an elegant take of “Annica”, the Buddhist doctrine of impermanence, which provides its title: “But we all must end/ so that others can exist. / That is the cost.” Another poem, “God is the Only Ghost,” carrying echoes of Ted Hughes’s Crow, tells us that

Sometimes he pretends that all stones

are bald heads half-buried.

[…]

God is scared to look Man in the eye.

He worries that in the dark pool of the pupil

there will be no one looking back.

The poems balance excitement and anxiety, creating a speaker with the tendency to be “alone in the quiet of it all” but compelled to “get on with all this living”. This latter becomes an urgent moral imperative carried in many of the poems’ titles – we must find “Sunshine in a Puddle” and “Wet Hot Happiness” because the alternative is “The Fear” or “Solitude.” It’s testament to the vitality of Lee’s verse that this message doesn’t feel hollow. The ideas aren’t always new, but the collection’s voice seems sincere and so they feel fresh. Taken together, they convincingly dramatise the speaker’s repeated attempts “to keep on living” and gain some knowledge of “God”.

Lee’s writing is alive and engaging with many memorable images. In “The Fear”, “Dawn breaks like a dropped teacup.” For the “Forgotten Gods” of the second poem, “A warm amber eye like a lion’s/ is the hole in the sky from where we fell.” She rhymes freely, but not jarringly, and the poems have a confident momentum. Alliteration holds phrases together musically, which is often effective – although potentially too heavy for some tastes – and sometimes, as in “The Fear,” picks up a tongue-twister-like quality:

I remember freckles on his face.

Each a speck of dust, still,

suspended in a slice of sunlight

in a white-walled space.

Lee’s phrases are consistently well-crafted in a way that her lines are occasionally not. Some end uncomfortably, splitting up clauses, pronouns from their objects, or ending on function words like “and” or “of”. This contributes to the lively pacing – the reader cannot linger on any one line, compelled to complete the image on the next – but readers tend to remember poetry in lines rather than phrases. The mnemonic function is somewhat diluted in these poems, making them less affecting than they might be.

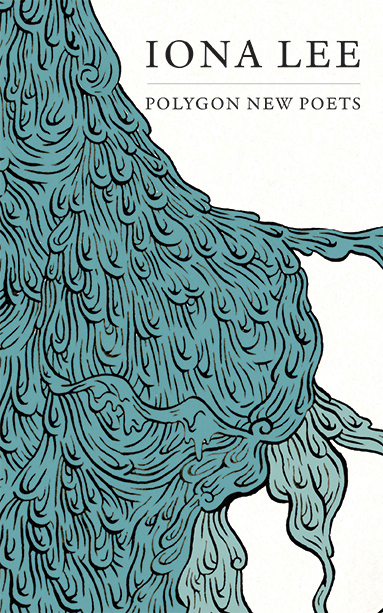

The pamphlet itself, published by Polygon in their New Poets series, is a lovely object. Lee’s own cover design is a colourful mass of something like seaweed. With fresh images and a compelling voice, this is a first pamphlet worth reading from a poet who seems likely to go on to create more imaginative work.