Opening a film with voiceover is always a risk. Often a hallmark of cliché, or just plain laziness, it can feel like audiences are simply being told what to think, instead of being shown. Yet in the case of acerbic comedy-drama Listen Up Philip, the sensation couldn’t be more appropriate.

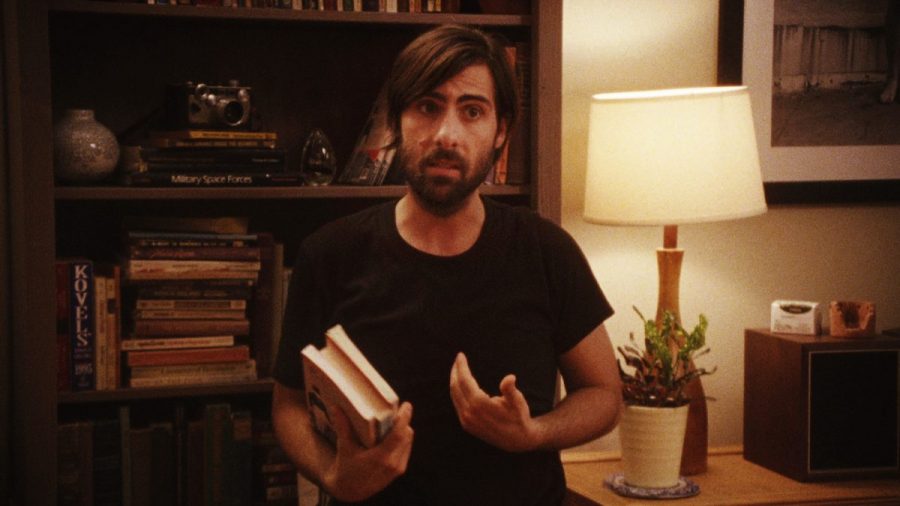

A novelist by trade, Philip Lewis Friedman (Jason Schwartzman) is egotistical, misanthropic and resistant to the feelings of others. Having his actions narrated in the third person only seems natural: the solemn-but-sympathetic delivery of Eric Bogosian a perfect fit for a man who behaves as if life starts and ends with himself – or at least the self he’d like to be.

Approaching the publication of his second book, Philip is eager to be seen as the real deal, though it’s not always clear who he’s trying to convince. He shares a Brooklyn apartment with his photographer girlfriend, Ashley (Elisabeth Moss), admiring yet not so secretly envying her success. It’s a pattern that colours his interactions with faces both old and new – from former flames, to creative writing students – Philip desperately seeks approval for his dreams, whilst callously dismissing theirs.

An encounter with his idol, veteran writer Ike Zimmerman (Jonathan Pryce) does nothing to suppress these instincts. Invited to the elder statesman’s country retreat, it soon becomes clear that the two have much in common, both latching onto people solely for those traits that make them feel good about themselves.

Met in reality, these men could sap the energy from anybody, but writer-director Alex Ross Perry ensures their company captivates us. Making clever use of a 16mm aesthetic, jazz score and heightened dialogue made believable by Philip’s ego (‘You need to be around sugar all the time,’ he scowls at one now content ex-girlfriend, ‘no wonder you’re a baker. You’re the worst.’), Perry’s film has the feel of a classic; it’s just how Philip would want his story told.

Yet the intimate, handheld camerawork reveals much more – especially in the excellent performances of Schwartzman and Moss. With every look of hurt and moment of reflection caught in lingering close-up, one thing is clear: Philip can view life through whatever filter he likes, but the damage he causes is all too real.