Mangrove is an interesting choice to open the London Film Festival. Technically a TV movie, it is the first episode of Steve McQueen’s anthology series Small Axe which is scheduled for broadcasting on the BBC in November. But that’s not to say that Mangrove is in any way televisual. In its own right, it is a phenomenal piece of socially-conscious British filmmaking in the grand tradition. Half kitchen-sink activism and half courtroom drama, this furious film about the pivotal case of the ‘Mangrove Nine‘ is unashamedly polemical, but its craft, lyricism and sheer power overcome any simplicities in the story.

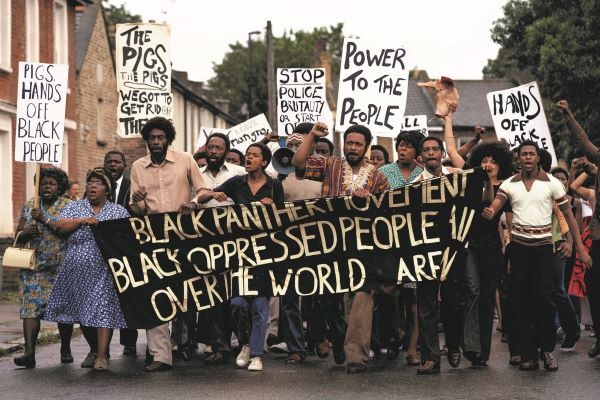

After Trinidadian Frank Crichlow opens the Mangrove restaurant in 1968, it becomes a focal point of the black community in Notting Hill. Subjected to continual, obviously racially motivated, police raids, a “Hands Off the Mangrove” demonstration was organised. There was violence and nine demonstrators were arrested and charged with numerous offences, most seriously the recently introduced charges of riot and affray. Among those charged were Crichlow, British Black Panthers Darcus Howe, Barbara Beese and Altheia Jones-LeCointe. The case became a cause célèbre as the first judicial acknowledgement of institutional racism within the Metropolitan police force. Mangrove covers the events up to the riots and the gruelling, attritional trial.

The film begins, aptly with the grand opening of the Mangrove itself, establishing it instantly as the eye of the storm that is to follow. The atmosphere is authentically febrile before McQueen sets up his central trio of Crichlow (Shaun Parkes), Howe (Malachi Kirby), and Jones-LeCointe (Letitia Wright). Mangrove deftly establishes his ensemble and their place at the centre of Notting Hill’s West Indian community. We’re left in no doubt how strong a bond the sudden, frequent, and brutal raids by the police are attempting to break. The police are represented by PC Frank Pulley (Sam Spruell), the venomous face of corruption and hate. Spruell has rather a thankless task, keeping Pulley within the bounds of reality while representing an entire monolith, but takes to it with gusto.

Parkes is our focal point as Crichlow; very much the reluctant leader. He becomes a figurehead purely through owning the business, and invites our identification as we reckon with our places within our communities. Parkes is so good that Crichlow’s quiet dignity is never overshadowed by superb turns from Wright and Kirby in more outwardly eye-catching roles. Wright’s Jones-LeCointe is the quintessential firebrand who we first see in an amusing scene preaching the benefits of trade unionism to an all-Asian (and all-male) room of factory workers. Kirby perfectly captures the heavy-lidded, leonine nobility that TV viewers would recognise in Darcus Howe in his later years.

The second half perhaps suffers a little in comparison as it heaves itself into the trial. The first half is so rich in details – Shabier Kirchner‘s cinematography brings the same grit and grain to London that Scorsese and Lumet did to New York in the ’70s, and there’s a heady aroma of kitchen sink revolution as well as fish, goat, and mutton curry from the Mangrove’s hobs. Once in the courtroom, McQueen is stuck with the familiar conventions of the format and doesn’t even try to subvert them. We’ve got the simultaneously Catholic pomp, ceremony, and ritual, with the Calvinist austerity of the proceedings themselves, and the grind of defence and prosecution cross-examining. McQueen keeps it simple and lets his cast do the lifting. Wright and Kirby are phenomenal as Jones-LeCointe and Howe represent themselves. Alex Jennings is the fusty judge, unaware he’s a part of history, and Jack Lowden is the defence lawyer for the rest of the nine. McQueen never forgets who his ultimate subject is however, avoiding any accusation of a white saviour narrative with ease and letting the moment of ultimate catharsis and vindication sit with Crichlow.

Steve McQueen is undoubtedly one of the finest directors currently operating. He’s known for his deeply human, intense character studies, but Mangrove feels like a continuation of his work on Widows. Not only does he expertly handle an ensemble cast, but it is also hugely entertaining. He has made the switch into a more mainstream and accessible mode without sacrificing any of his political drive or one iota of his quality control. Yes, Mangrove is an outright polemic, but no less valuable for that, and certainly no less relevant. Racism may wear a more polite face and be hidden beneath more reasoned language than when Frank Crichlow ran the Mangrove, but it is no less prevalent or virulent. Mangrove is an impassioned plea for vigilance from the grass roots up.

Screened as part of BFI London Film Festival. Airs on BBC Fri 20 Nov 2020