@ The Studio at the Festival Theatre, Edinburgh, until Sat 7 May 2016

The 1939 Gone With The Wind (GWTW) was one of the first Hollywood movies that showed just what could be achieved in the medium – it had wonderful characters, sweeping camerawork, cast of thousands and a new process called Technicolor. Max Steiner’s score became Hollywood’s national anthem. The film’s creation was famously painful. The screenplay, based on a bestselling bonkbuster, went through innumerable drafts (one by F. Scott Fitzgerald) and David O. Selznick, its producer, made a publicity mountain in casting the female lead, costs soared and at one time the project was almost scrapped.

Finally, its director George Cukor was fired and the production was put on ice while a script doctor, Ben Hecht, came in to save it. Leitheatre’s fast-paced production of Ron Hutchinson’s comic play (based on Hecht’s memoirs) is set in the office of Selznick (Kevin Rowe) as he briefs the writer Hecht (David Rennie), the only American not to have read the book. Hecht says he’ll rewrite the script but has only five days, a mountainous task as the book is a thousand pages long. The writer is not convinced as to whether it’s a “good bad book or a bad good book” and famously remarked that no Civil War picture ever made a dime. He was ultimately proved wrong when GWTW became one of the greatest motion pictures ever made and still stands up today.

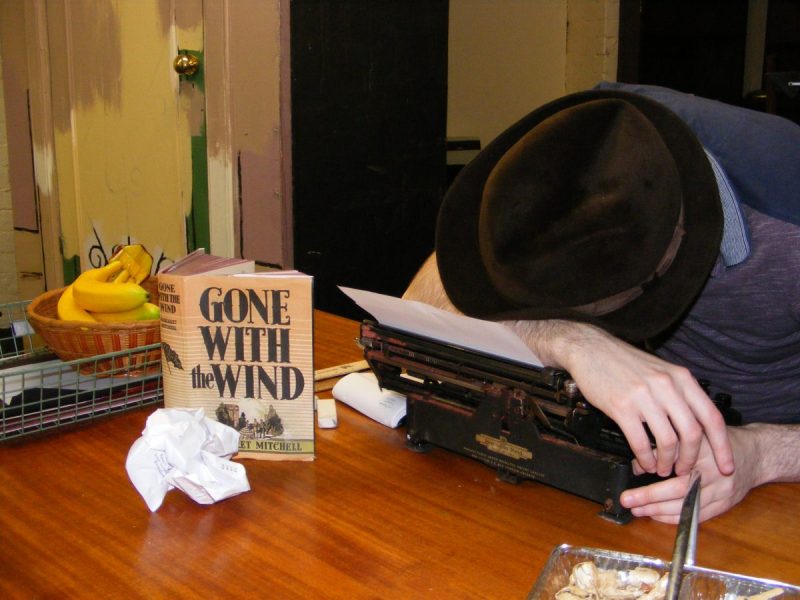

Into the mix comes director Victor Fleming (Josh Ingram) hotfoot from munchkin-wrangling on The Wizard of Oz. Together Selznick and Fleming act out the story with Hecht working his magic at a typewriter. Barbed antagonism ensues.

With energising bananas and peanuts supplied by Selznick’s secretary (a charming cameo by Elona C Smith reminiscent of Lily Tomlin’s character Ernestine) the two men’s interpretation of the roles of the flighty Southern belle Scarlett O’Hara and her dim maid Prissy makes for some hilarious moments. There’s some great observation too – how Jews, exiled from Nazi Germany, reinvented Hollywood; who is more important on a movie: the writer, the director or the producer; whether Hollywood should give audiences what they want or what’s good for them; and Hollywood’s yin-yang dilemma of well-crafted trash versus film art.

This truly is a locked-room drama – the action becomes more and more fractious as the days go on (and the office becomes a mess of banana skins and scrunched-up paper). The actors work hard to ensure this wordy comedy doesn’t become constipated or claustrophobic. Perhaps Kevin Rowe as Selznick might have been more passionate about his project and David Rennie’s accent was a little uneven. Minor quibbles. Rik Kay’s production might be too safe in places – there’s little sense of the crazy cynical thrum of Tinseltown back offices and the pace slackens here and there but it’s polished and professional.

Great insight into the production process! I never read the book either,but definitely fancy rewatching Vivien Leigh and Clark Gable getting it on after this.