Robert Webb is a difficult guy to entirely like. He was a voiceover in the irritating TV show Great Movie Mistakes about infinitesimally small movie continuity calamities and played Jez (against long-time collaborator David Mitchell) in TV’s Peep Show. Quite what makes Robert Webb think his memoir about growing up in comfy, lower middle-class, suburban Lincolnshire in the 1980s is worthy of recording is difficult to determine. His experiences have a universal ordinariness that can’t help but make much of the book border on the trite. And the humour is often ladled on with a bricklayer’s shovel. Teenage crushes, building dens, and playground bust-ups are the stuff of millions of childhoods.

Webb, however, writes well and the reader keeps going in the hope that there may be a gem over the page. Fortunately, there often is. What is far more interesting than assorted rites of passage are his observations about what is (or was) socially acceptable behaviour for boys and young men when Webb was a kid – big boys do not cry, hug, show emotion of any kind, or study hard. But Robert Webb was different. He tells the story of finding a bee in the garden struggling for life. He placed a protective ring of stones around the insect while most boys of his age would have stamped on the helpless creature.

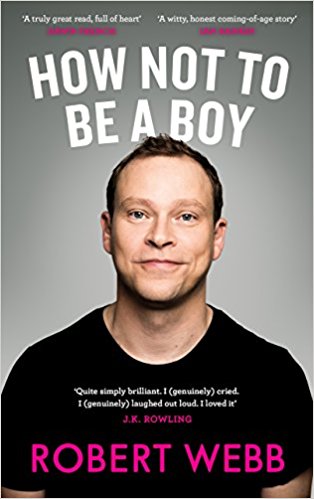

Webb was born after the brother he never knew died in infancy. He was the replacement. He was mollycoddled and spoiled by his doting mother (until her death of cancer) and photographs of the blond young Robert are positively cherubic. He had two much older brothers and a father prone to drunken rages. Webb’s childhood was a pretty solitary existence. He wrote in his teenage diary “Is there any romance greater than the one a teenage boy has with his own loneliness?” His depiction of the complicated relationship lots of males have with their fathers is bound to be familiar to many readers. If there had only been more of these insights.

His parents’ divorce clouded things but not materially so. He makes many wry comments and observations of growing up male and the various absurd strictures that must be accommodated lest lads appear weak or a pushover or just weird (or, worse at the time, gay). “There are probably lots of men who haven’t had their lives marred or pointlessly complicated by the expectations of gender, but I’ve yet to meet one.” Some of his observations are pretty sweeping, but there is a real truth here. He is critical of the way men are expected to “bury [their] pain, have to conform to the tribe; aren’t romantic enough; fail to do manly tasks with competence; make promises they can’t keep”. Small wonder that suicide rates for men are at an all-time high.

Maybe Webb doesn’t offer easy self-help answers to these questions of masculinity, but addressing them and writing them down in black and white gives them an almost shocking starkness. In one year alone he loses his father, stepfather, and grandfather. And his telling of his feelings is eye-wateringly honest. The real Webb is different from his TV screen persona.