“Do you remember the Harlem Cultural Festival in the Summer of ’69?”

That is the question posed at the beginning of Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson’s superlative Summer of Soul. Virtually noone does. Except those that were there. Over six Sundays, a series of free concerts were held at Mt. Morris Park in Harlem, each themed around a particular sound like blues, jazz, gospel etc. The concerts attracted a line-up of legends and figures from the forefront of black empowerment. The whole thing was captured wonderfully on film by filmmaker Hal Tulchin. Noone was interested when Tulchin tried to sell the footage, so he left the 40 hours of footage in his basement, where it was left in a basement for 50 years. 1969 instead became enshrined as the year of Woodstock, Apollo 11, Altamont, the Manson Family.

Hence that subtitle, …Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised, paraphrasing Gil Scott-Heron‘s proto-rap masterpiece. Questlove, in his directorial debut, has edited the footage down to some sublime highlights and interviewed many who were there; artists, organisers, and attendees. It’s an unabashed delight. Contextualising the event as a nexus of almost countless influences, Pan-African, Cuban, Puerto-Rican, Jamaican to name just a few, with a similar blurring of genres, the director offers the concerts as giddy and chaotic metaphors for Harlem itself. It makes it not just a magnificent concert film, but also a vibrant document of the cultural and social impact the festival had on those who were there. “’69 was the pivotal year in which the Negro died and the black person was born,” says one contributor. “We were radicalised,” says one particularly succinct interviewee.

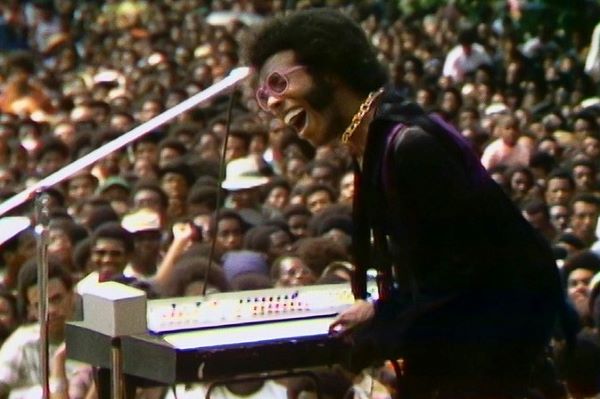

Highlights? Take your pick from this embarrassment of riches: BB King‘s ‘Why I Sing the Blues’, a phenomenal octave-leaping version of ‘My Girl‘ by David Ruffin, a young Gladys Knight with a slinky take on ‘I Heard it through the Grapevine‘, an electric, race-barrier busting Sly and the Family Stone with ‘Sing A Simple Song‘ and ‘Everyday People‘, a 19-years-old Stevie Wonder beating the drums like they owed him money, and an imperious, confrontational Nina Simone‘s ‘Backlash Blues’ and ‘To Be Young, Gifted and Black‘. For sheer power though, look no further than a duet between Mahalia Jackson and Mavis Staples on ‘Take My Hand, Precious Lord‘, the favourite song of Martin Luther King Jr., which goes beyond celebration into pure catharsis as Jackson howls pain, love, rage, and celebration at once. It’s a moment that crystallises the entire project. Togetherness and healing through music.

The section focusing on gospel is perhaps the most compelling of all. Black evangelism has always seemed more steeped in actual joy and love than you’ll see in your average Presbyterian tabernacle. Interviewees and performers like Al Sharpton and Mavis Staples point to the blues influences in Pops Staples‘ modern hymns and the assimilation of African ‘spirit possession’, into the music, giving it that sense of abandon adopted by several enraptured dancers in the crowd.

It seems almost unthinkable that Summer of Soul has been able to languish for so long, and some of that incredulity and anger inflects the film. Hal Tulchin died in 2017, but envisioned his footage as his legacy. Times have thankfully changed drastically, and it seems he’ll have his wish, albeit sadly posthumously. Given the rapturous reception for Sydney Pollack‘s digitally-salvaged filmed version of Aretha Franklin‘s Amazing Grace a few years back, and the highly-regarded status of Jeff Levy-Hinte‘s 2008 film Soul Power, about the Zaire 74 concert that accompanied the Rumble in the Jungle, it looks like the Harlem Cultural Festival’s half century in obscurity is coming to an end. We can only hope that Summer of Soul gets the biggest general release imaginable.

Screened as part of Sundance Festival 2021