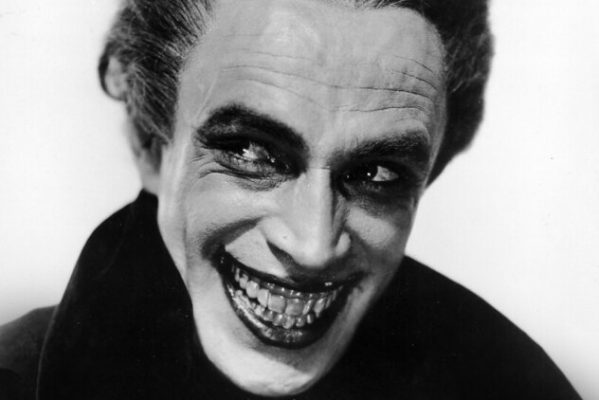

The Man Who Laughs has endured down the decades as an example of an early Hollywood horror film. Released by Universal in the few years before their iconic horror properties of the 1930s, it’s remembered for the rictus sardonicus grin carved into the face of lead actor Conrad Veidt. The star’s macabre makeup is behind its creepy reputation, which is otherwise wholly unearned. Rather than horror, The Man Who Laughs is a lush and heady Gothic melodrama that follows the Beauty and the Beast template, and deserves to be more highly regarded as a highlight of the late silent period.

In the late 17th century, Gwynplaine, the young son of a disgraced nobleman, has his face disfigured surgically into a fixed grin at the behest of the evil court jester of James II. A kindly showman (Cesare Gravina) takes pity on both Gwynplaine and the blind baby girl the boy has saved. Gwynplaine and baby Dea grow up to be star attractions in the travelling show (the pair are played as adults by Veidt and Mary Philbin) and are tentative lovers, despite Gwynplaine’s insecurity about his appearance. Their relatively peaceful life is shattered when Gwynplaine’s noble lineage is discovered, which draws the attention of Queen Anne, and the Duchess Josiana (Olga Baclanova), who holds the lands that are rightfully his.

The Man Who Laugh‘s place in cinema history is unfairly based on Veidt’s appearance being the foundation for that of the Joker in the Batman comics and subsequent TV and film adaptations. It’s a fine piece of pop culture trivia, but the film has qualities enough to cement its place as an important work. Not the least of these is the work of director Paul Leni, who ably straddles the tone between romantic period drama and the angular moodiness of German expressionism with aplomb, as well as serving up some spectacular crowd scenes that are the equal of similar, more lauded scenes in Sergei Eisenstein‘s Strike and Battleship Potemkin. That he died a year later is a particular tragedy given his evident talent. Perceived industry wisdom states he would have been in line – with his leading man Veidt in tow – for Dracula, which ultimately went to Tod Browning, and created an icon in Bela Lugosi in the process. Very much a case of what might have been.

The film also bridges some of the gaps between the fantastical designs of the earlier expressionist films and the more grounded talkies that were to follow, as well as the highly stylised, gesticulative acting of early film, and what we’re used to in the modern age. The sets are less angular and overtly nightmarish than those of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and Leni’s own Waxworks, while still being Germanic enough to also propagate the palpably Gothic tone. Veidt’s performance is soulful and all done through the eyes instead of theatrical gestures. There is also bubbling chemistry between him and the winsome Philbin. But there are undoubted moments of scenery-chewing, as you would expect. Baclanova – famous for her role as Cleopatra in the still-infamous Freaks – is enjoyably vampy and overtly sexual as the Dionysian Josiana, while Brandon Hurst is a study in eye-rolling villainy as Barkilphedro the jester, the principal antagonist. Overall though, the performances are fairly controlled compared to earlier silent movies.

There is the odd wobbly moment, including a sudden transition to swashbuckling adventure in the final act after an extended section of somewhat maudlin languor. This can easily be forgiven, however. Given that this is something of a transitory period in film, it’s surprising how complete it feels in its more rollicking scenes of derring-do. Leni employs many techniques that are still used constantly today so the film lacks the jarring quality that action sequences sometimes have in early films. The editing is tight and coherent, with the soundtrack by the Berklee Silent Film Orchestra a stirring new addition.

The Man Who Laughs is a fine work from the later age of silent cinema that is worthy of new appraisal. It retains much of the ambivalence to both the aristocracy and peasantry of Victor Hugo‘s source novel L’Homme Qui Rit, along with a structure that echoes other tales of revenant nobility like The Man in the Iron Mask and The Count of Monte Cristo. It is above all a plea for tolerance and humanity with a deeply romantic tone. It would make a good introduction to silent film as it contains many of the tropes of modern cinema, along with a simple, brisk story. The 4k restoration is beautiful, and Eureka’s Blu-ray package is customarily loaded with tasty extras. This a man to laugh with, not at.

Available on Blu-ray Mon 17 Aug 2020