Peter Brook is an internationally acclaimed director. So it’s an undoubted coup that EIF director, Fergus Linehan, has persuaded Brook’s theatre company, Théâtre des Bouffes du Nord to take up temporary residence in Edinburgh this August. Brook’s signature style eschews elaborate trappings and encourages his actors to draw on their emotions to connect with the audience.

True to form, the Lyceum stage is scattered with a sparse collection of sticks and stones which are called upon throughout the play to assist the storytelling. Costumes are simple but effective. Sound effects are minimal, meaning lighting director Philippe Vialatte is consequently given free rein to evoke time of the day, atmosphere, to add dramatic tension and, finally, to erode the artificial divide between artist and audience.

The story feels like a relic from a bygone era – or perhaps deliberately reminiscent of a Greek tragedy. A young man, Ezekiel, has been banished to a distant place for an “unspeakable crime”. One day, he returned home to find his father having sex with his sister. Overcome with rage, he kills his father.

His sister protests that she cannot forgive him as she loved their father. Ezekiel retorts, possibly not with the purest heart, that he loves his sister and couldn’t help himself. Hard to say whether this is a deliberate subversion of the Oedipus story, an archaic interpretation of gender roles or a statement in this #metoo age, alongside companion piece La Maladie de la Mort, designed to provoke.

Their uncle manages to extract Ezekiel from solitary confinement and arranges instead that he must sit outside a remote prison building and contemplate his fate. So Ezekiel sits. And night turns into day and day turns into night.

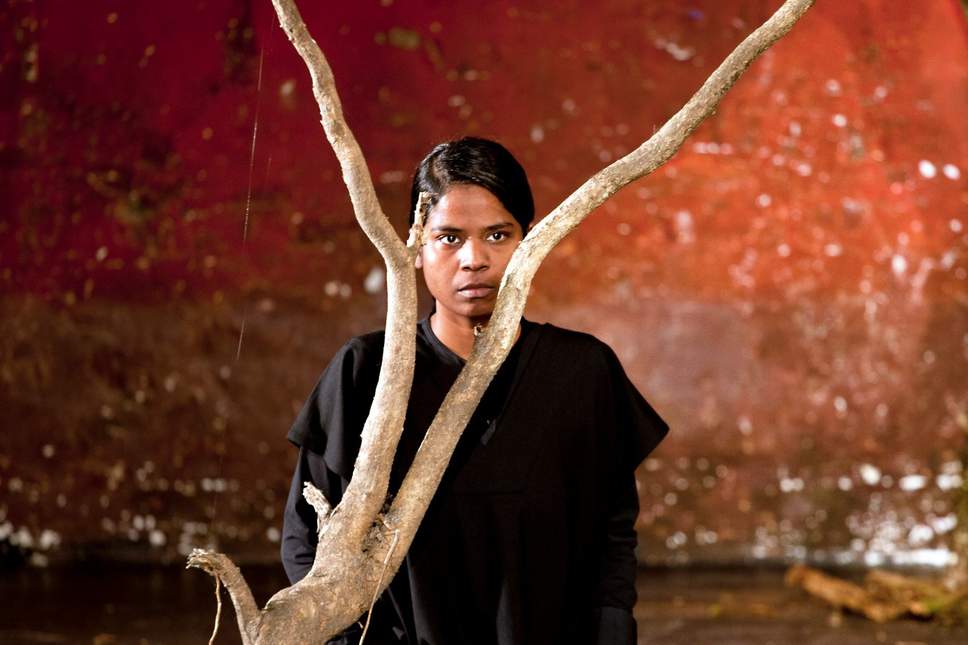

In spite of the cumbersome plot, the acting shines. Hiran Abeysekera is a wholly endearing murderous son. His bemusement in the face of the unspeakable crime is entirely convincing. There are some lovely moments: a brilliant use of one of the Lyceum’s boxes when his uncle takes him to a forest, and a captivating, funny attempt to befriend a passing rat. Kalieaswari Srinivasan is as genuinely touching as the script permits in her attempts to care for and console her brother. Hervé Goffings is a suitable forbidding uncle. Donald Sumpter brought a possibly intentionally colonial feel to his character though wasn’t always entirely audible.

The piece does raise some interesting questions. Is any prison worse than being trapped inside your mind? Are other people’s judgements more punishing than the law? Is company worse than loneliness? Are empty words worse than silence? And what passes for justice in the face of an “unspeakable” crime?

For my money, though it’s not quite the same story, Antigone did it better if you want to revisit ancient Greece. Even Kamila Shamsie’s novel Home Fire is better if you want a contemporary retelling brimming with relevance for today’s audiences. Nevertheless, The Prisoner is a brilliant demonstration of acting and a nice reminder of the magnetic power of silence.