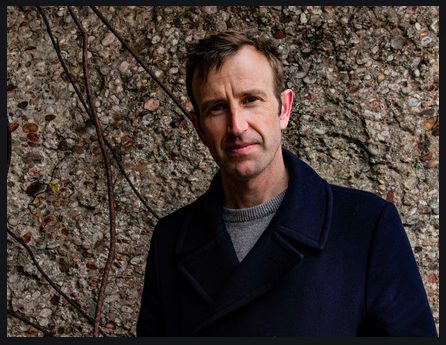

As one of the UK’s most prominent nature writers and critics, Robert Macfarlane has a history of creating thoughtful, thought-provoking books that give fresh perspectives on particular aspects of the environment and the Anthropocene. Previous focuses of his have included the language of landscape, explored in 2015‘s Landmarks, and the human desire to scale mountains, which inspired his 2003 debut, Mountains of the Mind, but today he’s here to talk about his latest work Underland: A Deep Time Journey, which looks at what’s beneath the ground we walk on.

Questioned about the writing process, Macfarlane explains that the book has been almost a decade in the making, and is roughly structured into three parts, looking at how the underland has been used to shelter, to yield, and to dispose. He talks eloquently about human interaction with the deep, and the varying range of responses people have – from feeling intense claustrophobia, to an instinctual pull – and his own experiences researching. His story of caving makes the subterranean sound like another world.

A central concern of Underland is how contemporary and past usage of the deep will affect not only the planet, but also our descendants. Macfarlane explains his preoccupation with the question ‘Are we being good ancestors?’, considering the ramifications of using the underland as a place of storage, particularly for nuclear waste. He touches on how the climate crisis involves the emergence of things that were intended to stay buried. As he talks a slideshow of images plays, portraying scenes mentioned in the book. One, portraying an enormous pinnacle of ice, hovers over Macfarlane’s head as he reads a passage recounting one of the uncanniest – foreboding yet beautiful – moments that occurred during his research.

Although Macfarlane doesn’t sanitise the more worrying events he explores, he acknowledges that his book includes unexpected moments of hope: his experiences with the Norwegian fisherman whose environmental activism centres the local community; the Finnish system for disposing of nuclear waste, which seems to be working surprisingly well; the discovery of the existence of a ‘wood wide web’, a system whereby trees are able to share resources and nutrients with each other. He explains the science behind this revelation briefly and engagingly, his own sense of wonder at and appreciation for nature palpable.