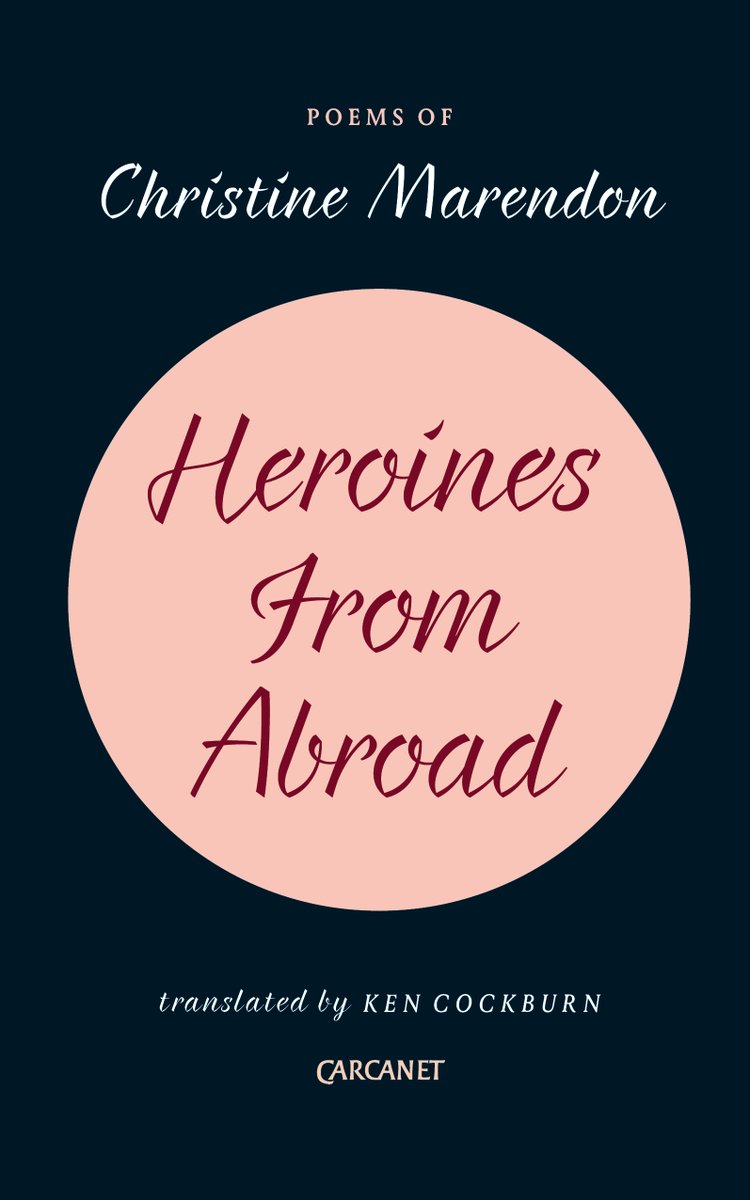

Heroines From Abroad is Christine Marendon’s first collection. Published by Carcanet Press, it is half-and-half German/English. The new translation by Edinburgh based poet Ken Cockburn launched at Lighthouse Books.

Raised in Bavaria and currently living in Hamburg, Marendon has a personal and individual approach: “I meditate and try to think of nothing. I don’t read other poets when I am writing. In this act of forgetting you find things you usually do not find; hear something you otherwise won’t hear.” With a distinctively female voice, there is a dreamy, Dali-esque quality, where apparently unconnected images circle around each other and leave the reader to make connections, to recognise something deep inside themselves. “I am only following my own logic”, Marendon intertwines her hands delicately, “not to hold, grasp it, but watch it and surround it with my words”.

Cockburn initially translated six of Marendon’s poems 13 years ago, saying it is the “wonderful coming together of images” that attracted him. “It was intriguing rather than frustrating that there were aspects which I didn’t get the gist of, that the poems created their own worlds with a kind of dream logic to them.” Indeed, as if on waking, a tumble of words related to half-remembered visions, or middle-of-the-night thoughts, co-exist. Fresh meanings emerge from already known words.

There are many recurring natural images – water, air, wind, and stone. In “Bahamut”, “I am the fish who, coming for air / kisses the water’s surface: / you see the disturbance, the circles it creates, but, me, the fish, / you don’t see”. When asked about the recurring imagery, Marendon stated, “I wrote these at different times of my life, they stand alone, but I am almost the same person, so there might be connections.”

The book title Heroines From Abroad is a phrase from “Rotunda” referring to Marendon’s family matriarchs. She explains that, in her experience, “Men are responsible for most translocations and women have to solve the problems and hold the family together when they get there.”

On the page the poems often have the appearance of prose with short, succinct phrases of two or three words. “The day, / forgotten. There at the edge. Where the darkness / lives.” The first few in-your-own-head readings do not reveal a recognisable rhythm, but hearing them aloud gives a more metrical sense. Cockburn states, “there was a rhythm I was trying to recreate in English.”

After reading, you will find that wisps of thoughts are ribboning through your mind.