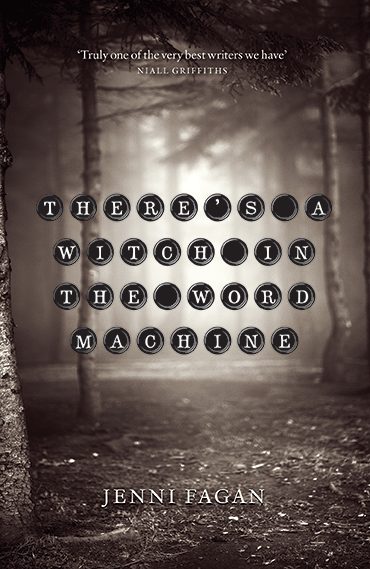

In Jenni Fagan’s newest compact poetry collection, There’s a Witch in the Word Machine, the intensity of language is starkly juxtaposed against the spare, bare layout of the text on the page. These are cries, howls, and screams against sorrow, betrayal, and being ignored in a world of 24/7 potential communication “whilst in another country/your lover once again/ignores you” (from “Spell for Someone Who Had Not Dreamt of a Unicorn Lately”).

The contradiction of enduring today’s news cycle against the persistent ache of loneliness is particularly well-observed, in particular in the honesty of the twelve-word poem, “Spell Written in a Square”, and in “Want”, which states “I can’t take them, nor/the news today,/… and for all I know/his cravings for me/ are already gone”. Technology cannot solve the universal conundrum of what another human being is thinking or feeling.

Some of these poems are devastating. “My House is Not My House” is bouncy and coy until the gut-punch of the last line. Individual images are arresting in lines like “I’ve had seven/months of walking/on the string of a violin” (“Spell for the Futility of Longing”) or “Parisian girls/take the swing of thin hips/as a gift from Venus” (“Spell for Loneliness in Paris”). There are many more to be savoured. And that is, perhaps, the way with a book of poetry. Each reader chips out what they find most pleasing to store away for another time. Should this work be read cover to cover? Definitely, and in doing so it carries a great weight that brings tears, but afterwards there is a joy to dipping in and out, getting to know the poems and what each can deliver.

There is an autobiographical slant to many of the pieces. Some were written while Fagan participated on the Outriders Project, part of 2017’s Edinburgh International Book Festival. Others while in residence at Shakespeare & Company in Paris. And more, like “Spell for Someone Eternally Restless”, seem to speak to a more enduring uneasiness.

“Bangour Village Hospital” is the longest piece in the collection and is much more than a straightforward poem about where the author was born. A short film written and directed by Fagan is available and hearing Fagan read her own work, giving her own weight to her words and pauses, is both original and extremely powerful.

Some readers and poets might not savour such short lines, sometimes only containing one or two words, but, when being precise, when cutting to the chase, telling it as it is, brevity is all.

There’s a Witch in the Word Machine’s sparseness makes it accessible to read, while the precision of feeling and observation reveals depths of universality. This is powerful poetry that deserves a broad audience.