(Published by Canongate, £25)

Before the Grammys, before the MTV Awards, before the Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall of Fame, the ultimate accolade, if you were a rockstar, was to get your face on the cover of Rolling Stone magazine. Dr Hook even sang about it. This biography is of Jann Wenner, founder of the magazine that began life in San Francisco in 1967 as a mouthpiece for the burgeoning counter-culture. The first cover was devoted to John Lennon (Dr Hook got their shot in 1973). In the succeeding 50 years the magazine evolved, its format changed and it became far less radical than it was when it began. Its production values vastly improved and its long-form journalism matched that of anything in the New Yorker or Time. The magazine has covered everyone over the years from Ozzy Osborne to Obama, from the Grateful Dead to Rihanna.

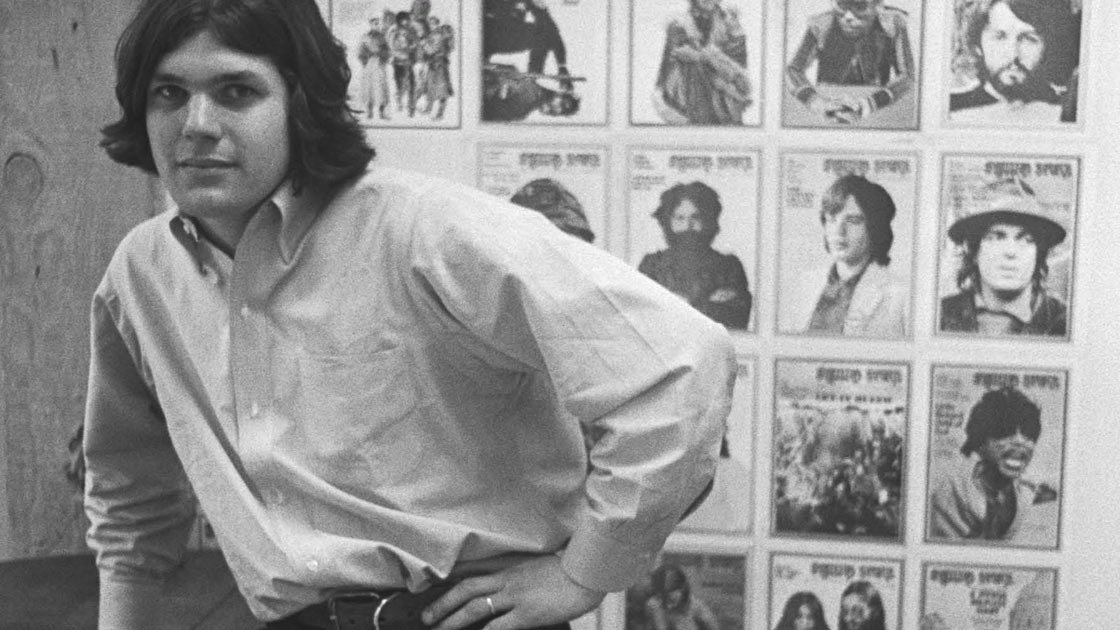

Wenner also evolved over that half-century from a 20-year-old hippie whizz kid to the overseer of a multimillion dollar publishing empire, from a family man to one of Out magazine’s Power List (he came out in 1995 and left his wife of 26 years).

From the very outset when a nice, middle-class, industrious Jewish boy with a business mind wanted to be “the Henry Luce of the counterculture”. Despite the yippie freeks around him he talked of limited liability shares and 15% returns as he hustled for investors and advertising money. In his pitch he described what Rolling Stone was going to be all about: “the magic that sets you free”. The pages were to feature not just record reviews but be of the lifestyle, politics and culture of the moment. But he didn’t want some hippie rag – it had to be well designed, well written, authoritative and, above all, professional.

The first quarter of the biography is a wonderful evocation of the dawning of the Age of Aquarius from its ground zero. Huge crowds at the Monterey Pop Festival in 1966 got Wenner thinking that a magazine aimed at these people – university educated, suburban, white, mainstream, mainly male, average age 21 – would be a surefire hit. And readers responded, as much to the crits, interviews, news of record deals and band break-ups as to the rather preppy layout – white space, Oxford borders – a style curiously at odds with the psychedelia of the time.

Wenner was reluctant to let the magazine get too political even as students got shot on campus and there were riots in the streets. Wenner always professed to be the supreme fan boy – especially when it came to John Lennon. He commissioned writer Hunter S Thompson and splatter cartoonist Ralph Steadman and the three of them pretty much invented gonzo journalism. Other notable contributors included Jan Morris, Tom Wolfe and Annie Leibovitz, who became house photographer.

The book is no hagiography. It covers the mercurial Wenner’s troubled and unconventional marriage, his drug taking, hyperactive personality and assorted feuds (with famous names like Joni Mitchell, Mick Jagger, Elton John, the Eagles and even John Lennon). Wenner somehow managed to patch things up again. He could be a bully to staff, a control freak and cheapskate but also charm the socks off anyone. Tom Wolfe said Wenner “was pretty much immune to guilt”. All the while Wenner loved the music. He is often described in the book as the ultimate groupie.

There was always a battle at Rolling Stone between music and mammon. “Wenner had never been, exactly, revolutionary,” says Hagan. “He wanted to overthrow the establishment by becoming the establishment.” America is famous for magazines (some long-forgotten) like Life, Look, Holiday, Esquire, Talk, George, The Saturday Evening Post, Collier’s, all of which captured the zeitgeist at one time or another and whose time was up.

Rolling Stone‘s trajectory is a strange mirror of contemporary society over the last half century – from the hopes, freedoms and radicalism of the 1960s to today’s pasteurised, prepackaged culture dominated by big business. Yet from the start Wenner wanted to make money. Lots of it. Even when they couldn’t afford it, Wenner and his wife lived pretty high on the hog, with a luxurious home in Pacific Heights and a Porsche, while staffers grumbled about low pay. “Who else loved Jann Wenner but Jane [his wife] the co-owner of the only thing he cared about, Rolling Stone,” writes Hagan.

In the early 1970s the magazine’s finances were on an increasingly shaky peg. By then in many people’s eyes the it had sold out. It bore lucrative ads for low tar cigarettes and steel belt radials, not to mention the big record labels who could pull their advertising if they didn’t like the music reviews. Rolling Stone became as Hagan puts it “the industry turnstile through which one passed to sell records in America”.

A turning point was the magazine’s coverage of the 1974 kidnapping of Patty Hearst – the heiress granddaughter of William Randolph Hearst, Citizen Kane himself. A report of her year on the run with her abductors appeared in Rolling Stone the very week she was finally caught. It was one of many coups, another being the year-long serialisation of Tom Wolfe’s groundbreaking novel Bonfire of the Vanities. In 1980, Annie Leibowitz photographed John Lennon hours before he was assassinated and her photograph of a clothed Yoko and naked Lennon made the cover of the magazine.

A move, by 1980, saw the magazine sashay away from music to movies, TV and celebs and “general interest”. It began to look flabby and no longer the hip cult it had once been. A move of offices to New York and Wenner’s increasing cocaine habit didn’t help. Wenner had become the antithesis of the hippie early-adopters of Rolling Stone back in 1967 – he had a summer house in the Hamptons, vacationed in the Caribbean and owned a Gulfstream jet. When he ran an ad campaign for Rolling Stone aimed at informing the advertising industry of the magazine’s readers, one side of the page had the headline “perception” (a peace symbol), the other “reality” (a Mercedes logo).

Hagan gleefully records the fluctuating fortunes of Wenner and his music bible. A 2014 story about rape accusations at the University of Virginia landed the magazine in the libel courts and when the Boston marathon bomber appeared on the cover he seemed to look like a rock star and caused another furore. Wenner didn’t fully understand or appreciate the coming digital age which perilously has eaten into print media circulation figures everywhere.

Wenner allowed his biographer to access all areas of his life. The New York Times reported recently that Wenner dislikes the result. It’s certainly warts and all. But the book is hugely readable (although there sometimes a tad too much business detail) and will stand the test of time.