Illegally crossing the border into America isn’t the end of the trials migrants face when desperately seeking a safer, more stable way of life. For Miko Revereza, twenty years after first arriving in the States, travelling anywhere comes with added risk. In making an urgent foray from Los Angeles to New York, the solitary train journey highlights the fragile nature of his and other immigrants’ status as border patrols and hostile attitudes become more persistent in America.

Since leaving the Philippines as a young child, his family has meant everything to Revereza – particularly his mother. They talk daily, on two phones no less; one for everyday discussions, another with no data plan or contracts to discuss immigration. No Data Plan follows Revereza’s journey from the perspective of his camera phone, with only momentary shots of Revereza himself as he desperately send out messages on how to avoid answering questions from border control. Over the visuals of cityscapes, setting suns and train conductors, conversations between Revereza and his mother address the fears they share as hostility towards immigrants becomes more open in America and reminds us just how easy some of us have things.

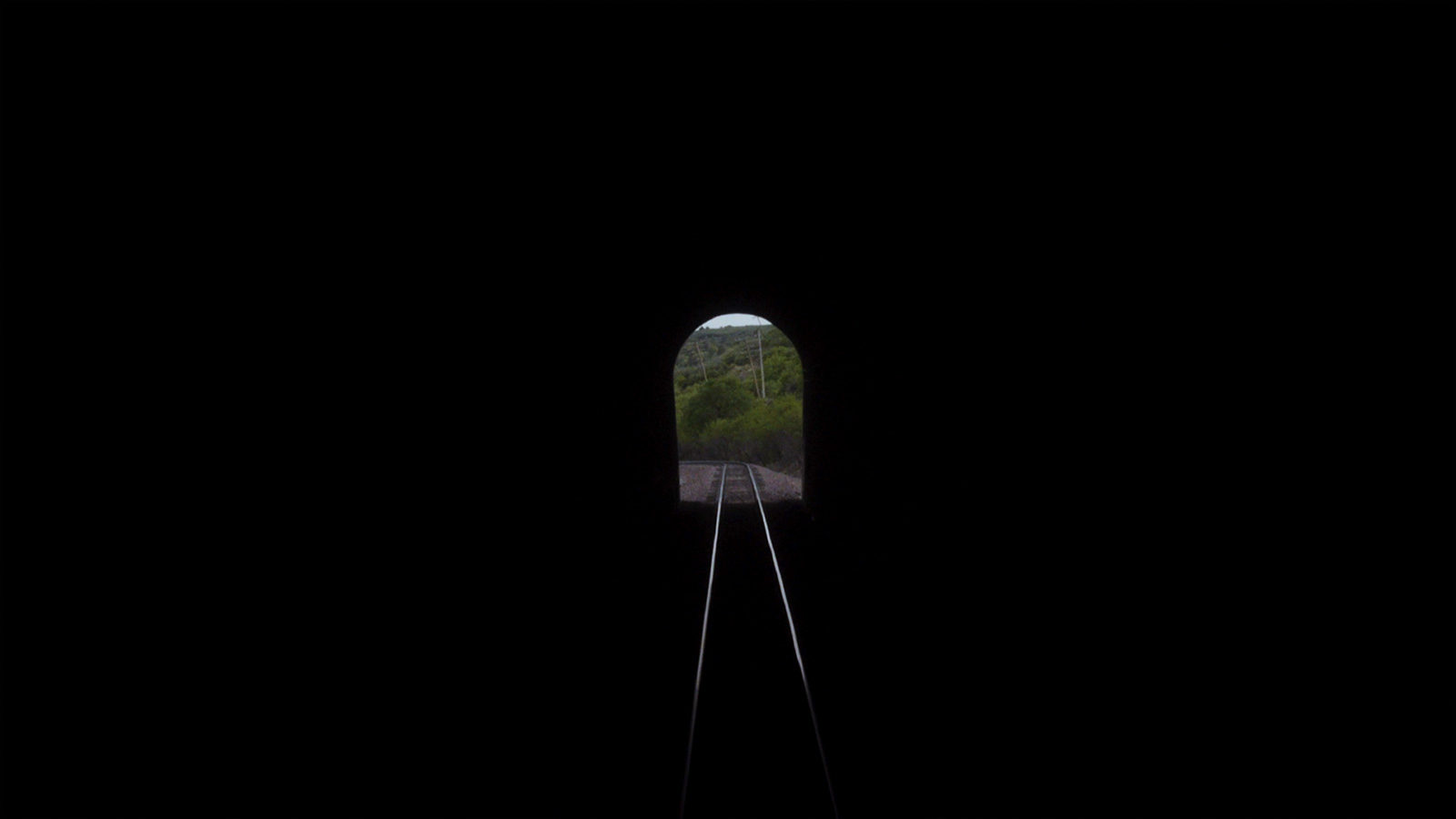

Hypnotic, the incessant anxiety Revereza conveys as the camera flickers to and from the carriage entrance or out the windows unknowingly sets the heart racing. No Data Plan’s ability to transfer Revereza’s emotional state without traditional dialogue is admirable. Save for train workers or passengers, the film is spoken entirely in Tagalog with subtitles, as Revereza ruminates on his life trajectory and its associated concerns.

The shift in traditional storytelling does come with a cost. If it grasps the audience’s attention, No Data Plan will land hard, but it has to make an impression first. Far from a background film, Revereza’s story requires attention and respect for it to work. Though the cross-country journey can occasionally provide scenic shots or snippets of adrenaline, much of this journey is mundane. Though it effectively reflects how even a simple trip can change Revereza’s life, the hour-long shots from inside a train carriage detract somewhat visually, even though there is some creativity in the cinematography.

For those who want to make the great American rail journey on the cheap, it’s an excellent cost-cutting way to see the many sights of seven-elevens, landfill, urban waste and, yes, more landfill. But partly, this image ties directly into Revereza’s words of the desperation to make it into America, to seek not simply the flawed and broken American Dream, but just as a means to escape. ‘The Land of Freedom’ shot from the train is neither one of amber waves of grain nor one of hope and glory, but is instead obstructed by telephone wires and fencing, reflecting the tightening restrictions and attitudes towards immigration within the US.

No Data Plan ends much like Revereza’s future: without certainty. Rocketing from the train yard and fleeing from border patrol (though we are unsure if they have spotted Revereza) without turning back, the camera cuts as we turn a corner. The words of Revereza’s concerned mother, a woman who wants nothing other than her son’s safety, hit with a sombre note of deflated hope. Authentic, and with only minimal editing, No Data Plan is a condensed state of anxiety looking to create an augmented experience of an immigrant looking to secure his and his families future.

Screening as part of Document Film Festival 2021