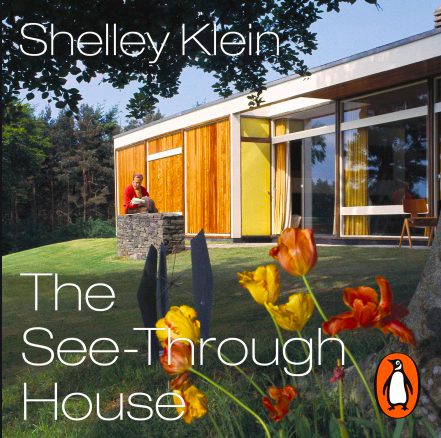

Most of us would struggle to describe the places we live so fully as to fill 288 pages but when you live in one of the foremost modernist homes, designed by renowned architect Peter Womersley, there is just so much to describe.

Shelley Klein’s first work of non-fiction takes the reader on a journey through her childhood home exploring precious memories and poignant moments; touching on grief, the histories that make us and the artistic genius of her father, the Serbian textile designer and artist, Bernat Klein.

Much like the house, she describes the story of High Sunderland in Selkirk and its members in a free-flowing, open-plan style; each chapter taking a different room and dissecting the importance it held with charming anecdotes of how her father saw it, the love of her parents and the feelings the different parts of the house evoke.

What truly brings the house to life though is the exquisite descriptions which bring the reader right into the heart of these rooms. The living room, for example, is described as being entered, “much like one might enter a swimming pool, that is to say by descending three shallow marble steps…Also, much like entering a pool, the room swims with light…Beech and pine trees sway gently against bright green lawns providing a backdrop of shivering emerald. This is a room in which to relax, in which you can float, in which you can allow your mind to drift and here, in turn, is another trick of the house in that during the day it expands to encompass the outside landscape while when night falls and the curtains are drawn, the house retracts, draws into itself and exudes only warmth.”

The house was everything Bernat Klein wanted and yet there are amusing conversations interspersed in the text which show it wasn’t perhaps the most practical place and his views were the only ones to be considered inside the house. The burning of a coat gifted to Shelley because to him it was ugly perhaps the epitome of these clashes.

He was a man who had faced hardship in his life, not least losing his beloved mother during the Holocaust but his passion for colours, fabric and design, and his interminable desire to keep looking forward made Bernat Klein a very special man indeed. His loss was felt deeply by his daughter Shelley and in the pages of this book she brings together some of her most special memories of the man who saw his life through the lens of this very special house.

The See-Through House is a beautiful testament to a father-daughter bond, an exploration of the complexities of grief and, all together, a quite stunning account of a one of a kind house.