At the Edinburgh Filmhouse on Wed 17 & Thu 18 Oct 2018

“You can’t sing. You can’t play. You look awful… you’ll go a long way.” So ran the old KitKat ad. The Go-Betweens didn’t go a long way, but their self-assessment is similar, up to a point. “We didn’t look the part. We didn’t sound the part…,” says drummer Lindy Morrison. “We were too intelligent.” Those facts, especially the last one, are borne out frequently in Kriv Stenders’ impeccable rockumentary of the band. Spearheaded by the twin songwriting talents of Robert Forster and Grant McLennan, they may not have sold well, but they’re Australia’s most fascinating, perhaps even greatest group.

The portentous three note opening of their most famous work, Cattle and Cane, also opens the film. It’s stretching it to say their career is defined by those notes, but a fair summation of it is encapsulated in their aching beauty. Cattle and Cane is to Brisbane and Queensland what Love Will Tear Us Apart is to Manchester and Pennine Lancashire. It emerged from and of the landscape, a landscape that Stenders makes ample use of to contextualise this singular group. Band members are made to announce their arrival or departure from the narrative by strolling into or out of sight down a long driveway, through fields, like Gladiator Maximus in his dream sequence or Scarlett surveying Tara. They then sit, still and beautifully framed, on the front porch to talk. Horses loll in nearby fields. Breeze rustles the trees. It’s quite the most evocative setting.

Meanwhile, talking heads of friends and acquaintances, shot black and white in a studio, are numerous, candid and well-edited. McLennan’s sister provides emotional breadth and depth to the film, talking of her father’s, and ultimately, Grant’s early death. Contemporary scenesters offer their tales and minor rock royalty pay homage, but not just out of duty. They know their stuff, and they care. Thus we get Bad Seed and Birthday Partyer Mick Harvey praising Morrison for embossing the odd rhythms of the boys’ songs (“She never straightened anything up ever”) and Lloyd Cole, of all people, waxing lyrical about how Forster was pop’s Samuel Beckett.

Friend and writer Clinton Walker is particularly good value. Before them, he says, Australian music was all “beefcake”, while the Go-Betweens were “a pair of poofters… of course they had a woman drummer!” The affectionate and impolitic mockery continues. He thought the Spring Hill Fair album was a “turkey” and told Forster so to his face (it’s far from it, but you take his point). “Someone needed to take his cherry,” he says of Forster’s early romance with Morrison. He metaphorically facepalms every time he remembers them adding another ego or volatile personality to the “cauldron” that was the band. The unguarded comments of a friend like Walker probably acted as a powerful corrective to the band’s tendency for seriousness and overthinking. And yet he too is moved to tears by their music.

When the needle hits the vinyl to introduce Cattle and Cane properly, it’s our turn to be moved. The camera cuts to horses in fields. A friend tells how he had to pull over to the side of the road when he heard it, his hairs standing on end. Yours should too. It’s time-stoppingly beautiful.

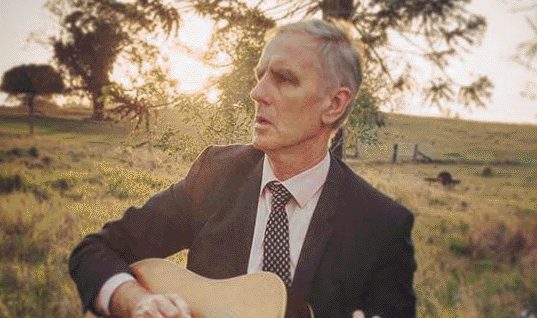

Stenders has really got beneath the surface here, and found visuals that work on you the way the band’s music does. Forster, now a trim, silvery gent in high quality tailoring, has always cut a striking figure. Stenders has him beaming long silent stares into the distance, or pacing the estate with acoustic guitar like a shotgun. He’s not the only one to get that treatment. Morrison pauses uncomfortably while talking of Forster, licking her teeth as if thinking over whether to reveal something rude or tragic. It’s his shirt. She’s only remembering his shirt. But with such clarity, we see her soul. This recollection isn’t mere factual memory, it’s something she’s living now. That merging of past and present is something the Go-Betweens pull off in their music. Songs slow the march of time to a crawl, so that ancient memory feels like current reality. They belong to the 1880s as much as the 1980s. Stenders has intuitively understood that.

On the factual side, we learn that Australian music had its own Lesser Free Trade Hall moment when Laughing Clowns, The Birthday Party and The Go-Betweens all appeared on the same bill, a gig that now seems like Australian alternative music’s year zero. They found themselves at Scottish indie’s year zero too when the boys from Orange Juice got them a deal with Postcard Records, a connection that makes perfect sense. Edwyn Collins and co never looked or sounded the part either. While Orange Juice were aiming for Memphis soul and missing – beautifully – the Go-Betweens were doing much the same with melodic pop. Eventually the band ended up on Rough Trade, but the label’s love affair with those other indie fops the Smiths pulled the rug out from under the band for not the first or last time, Geoff Travis dropping them to turn his energies to Morrissey and Marr.

Far more than the career details though, it’s the contradictions in the characters that prove most fascinating. Morrison, we’re regularly told, was a “force of nature” and difficult to work with. You can see that on occasions – the way she cynically mugs to camera on pop show Countdown for instance. Yet in interview, she’s often gentle, almost bashful. Her now age-lined face is kindly, like that of a wise spiritual healer. The late McLennan, we’re told, was “not lonely… [but] alone” in the world, fixated on the tortured-artist-in-the-garret myth and an on-off heroin user. Yet to the eye, he’s always looked like a boring everybloke who’d come round to fix your telly. Forster is outwardly a paragon of over-serious, ego-driven masculinity. Yet here he is in lipstick and eyeshadow, or camping it up in a crop-top on the video for Head Full Of Steam, or cross-dressing with McLennan and Morrison for a promo pic in the style of Queen’s I Want To Break Free. None of them are simply understood.

As a result, the band dynamics are much richer and more nuanced than is commonplace in rock biography. Forster and McLennan were, to quote a well-worn phrase that’s used once again in the film, the “indie Lennon and McCartney”. Yet the Yoko and Linda in this instance – Morrison and multi-instrumentalist Amanda Brown – were not only both in the band, but raised on pragmatic 80s punk feminism rather than 60s hippy idealism. They were no-one’s WAGs for sure. If anything, the Go-Betweens were the indie Fleetwood Mac. Liberty Belle was their Rumours (commercial peak, fuelled by relationship implosion), Tallulah their Tusk (over-reaching, broader instrumental palette), 16 Lovers Lane their Tango In The Night (calculated and radio-friendly).

Forster had formed a band with McLennan because of who he was, not what he could play, so his insight into McLennan’s growth as a songwriter is illuminating. He talks of seeing McLennan approaching in his rear-view mirror as he grew in stature, passing him with Cattle and Cane.

The partnership is placed under strain by McLennan’s romantic and creative connection to Brown, but reasserts itself ill-fatedly after 16 Lovers Lane is released. They decide they want to go back to basics – just the two of them together. In a telling scene, the two women sit at a kitchen table to reveal what they thought about that. Brown remains incredulous. How was McLennan complacent enough to think their relationship would survive a brusque dumping from the band? Morrison is rankled at how they were cast aside like the WAGs they patently weren’t.

Had the band survived into the 90s they could have been an R.E.M. We’d be talking of their 80s albums the way we do of Document or Green. That they didn’t is both curse and blessing. It leaves their 80s output frozen and unimpeachable. It also allowed them the too brief lap of honour in the noughties that ended with McLennan’s untimely heart attack, shortly after the release of their most successful album, Oceans Apart in 2005. But it meant the promise of superstardom never materialised. Not that all the band minded. “Weren’t you upset you didn’t get a Top 40 hit? No, that wasn’t my dream,” says Morrison.

She is of course right – they didn’t sound the part, they didn’t look the part. Yet they were all the cooler for that. In every press shot shown here they look mismatched but oddly captivating. You wouldn’t have them as pin-ups on your bedroom wall, but you’d hang them in a gallery. What Right Here makes clear is that the Go-Betweens were true artists – weird, mysterious and brilliant. After 95 mins in which they’ve told all, they somehow remain inscrutable. They weren’t the biggest band in the world. They were much better than that. And the fewer people realise it, the better to preserve them.