The music in Jim Jarmusch’s films can occasionally drown them. In Only Lovers Left Alive, the insistent droning of the soundtrack’s guitar begins to grate the senses, but when the filmmaker has the right measure, something lovely happens. The films themselves become musical: whether in the rhythms of the editing, the repetition of images and symbols which play out like musicals motifs, or something which is simply impossible to describe, just like music. It’s its own language.

The Limits of Control fits this description, but there’s something missing. The film is a mass of referents and cultural revisions, and while, in the director’s worst efforts, it’s possible to write off his referentiality as one of the symptoms of his type of cool-worship, here, and in his beautiful, open Paterson, the scheme of the film is more promising. A early quotation from T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land (‘a handful of dust’) provides the hint: The Limits of Control is a modernist movie in which the shards and pieces from other movies, books, music, paintings, and buildings create a new whole. It invites another line from Eliot’s poem: ‘I have shored these fragments against my ruins.’

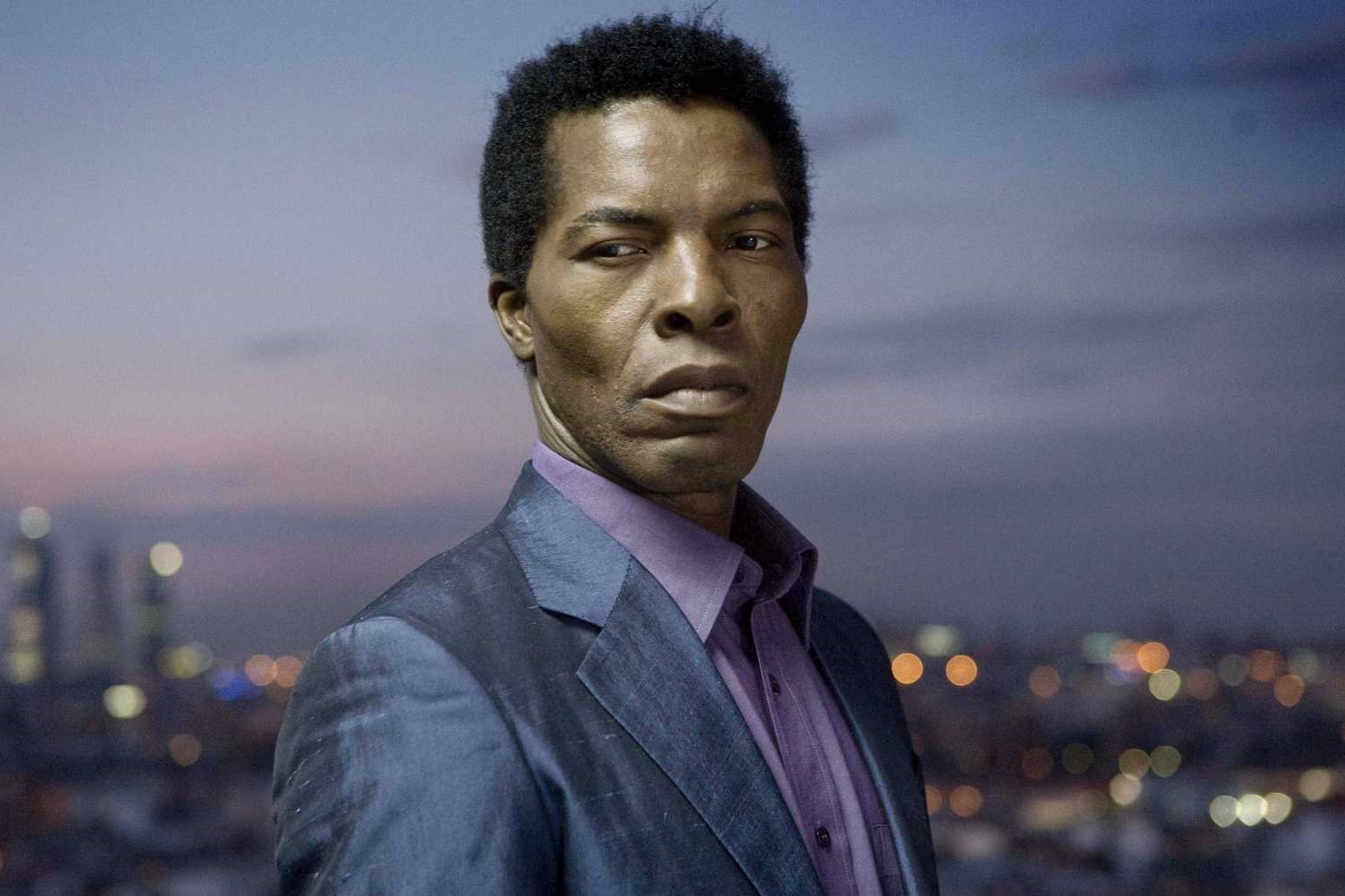

The fragments are the following: Lone Man (Isaach de Bankolé) is on a mission, delivered to him by Creole (frequent Claire Denis player Alex Descas), who gives the first in the film’s long line of cryptic advisory sentences: “The universe has no centre and no edges.” Helpful? No. Not at all. Lone Man travels to Madrid, drinks in cafes and meets a string of people who ask him if he speaks Spanish. When he replies, “No,” they trade a pack of matches, containing inside a sheet of paper with an indecipherable message. These seem to point him in the direction of his next meeting, but the logic of the film is not where its pleasure is found.

Its pleasures are its profound narrative piss-taking; the film’s series of sand-dry cameos (from Tilda Swinton, John Hurt, Gael García Bernal, among others); Christopher Doyle’s superb cinematography, which itemises a world of objects and arranges them in preposterous concert; and de Bankolé’s performance — his dapper frame gliding through scenes with supreme nonchalance, a contemporary and less cynical Jef Costello from Jean-Piere Meville’s Le Samouraï. The Madrid section, in its quietude, has the feeling of José Luis Guerín’s In the City of Sylvia; yet, this is mixed with a James Bond-like spy-thriller scheme and its attendant location-hopping.

But the pleasures have their limits, too. There’s a character, played by Paz de la Huerta, always sans clothing, who amounts to a Godardian Bond-girl. (That’s like sexism squared, Jim.) Also, Tilda Swinton’s cameo — she’s named only as “Blonde” — is where the film looks most like eating itself: she’s wearing a cowboy hat, has straightened hair, red lipstick, a trench-coat, and leopard-print boots on. You can almost see the director watching the rushes of her takes, removing his shades, and whispering into the air, “cool.”

And yet, while Lone Man’s mission “progresses,” and its apparent objective comes into view, Jarmusch’s patterns redouble and reveal themselves in odd and usually delightful ways, and it’s Swinton’s appearance which best accounts for this. Although self-indulgent in an Ouroboros fashion, the scene includes a discussion about dream-work and its similarity to film-work, and raises the question as to whether there’s a genuine difference. For all the preciousness of Jarmusch’s films, for all that their self-acknowledging conceits may fall apart if thought about for a moment too long, The Limits of Control achieves something not many films do, or can: it feels like a movie dreaming about itself.

Available on Blu-ray now.